Mark Newport and Jane Lackey: Correspondence @ Simone DeSousa Gallery

Installation image out front of Gallery. All images courtesy of Simone De Sousa Gallery

Former Fiber Artists-in-Residence, Mark Newport (2007-2023) and Jane Lackey (1997-2007), who served long tenures at Cranbrook Academy of Art, have reunited in a two-person exhibition at Simone DeSousa Gallery in Detroit. Though both have developed singular practices and careers, their show, self-titled Correspondence, showcases underlying similarities in their art-making processes. Indeed, despite their physical distance from one another–Newport works in the Detroit area while Lackey has resided in New Mexico since 2009–they remain in touch and together initiated the exhibition concept.

Installation view of Mark Newport and Jane Lackey: Correspondence

At first glance, observing their art on opposite walls in the main gallery, one might think the two clusters of art represent antithetical points of view and execution. Newport’s robust stitchery versus Lackey’s inclination to highlight the process of flowing; his darkling monochromatic palette, her startling cobalt blues; his army blanket supports, her meticulously hand-drawn grids on paper; his gnarly surfaces, her neat, calm meshes; his irregularly shaped compositions, her Spartan rectangles.

Yet correspondences, as Newport and Lackey remind us, emerge upon further viewing: their vertical compositions convey a kind of order and classical uniformity; asymmetric shapes and forms enliven and colorize the pictorial spaces; both employ open ended, ad hoc creative techniques; and repetitive titles emphasize the seriously serial explorations of mending and flowing, the common but enthralling modus operandi of these two makers.

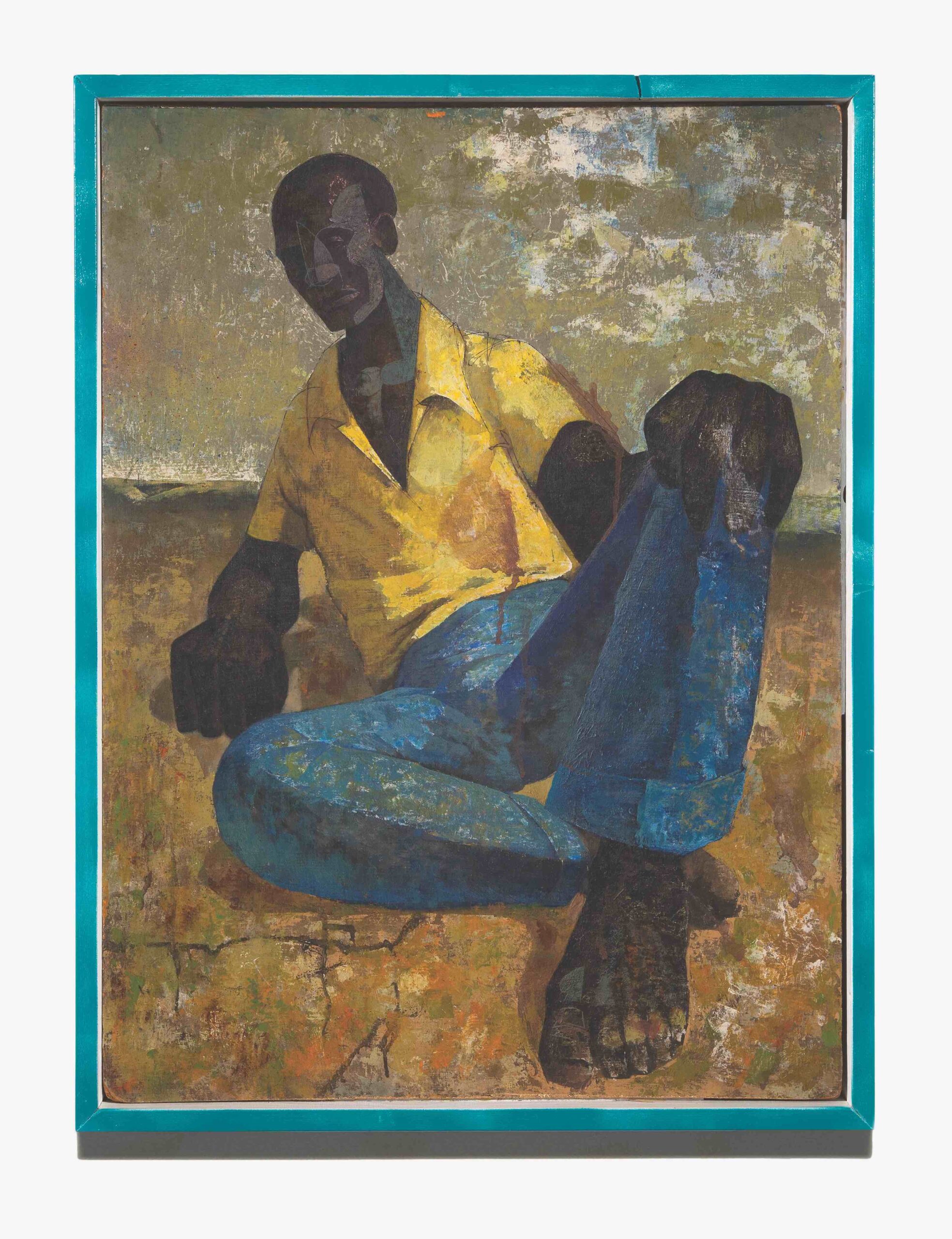

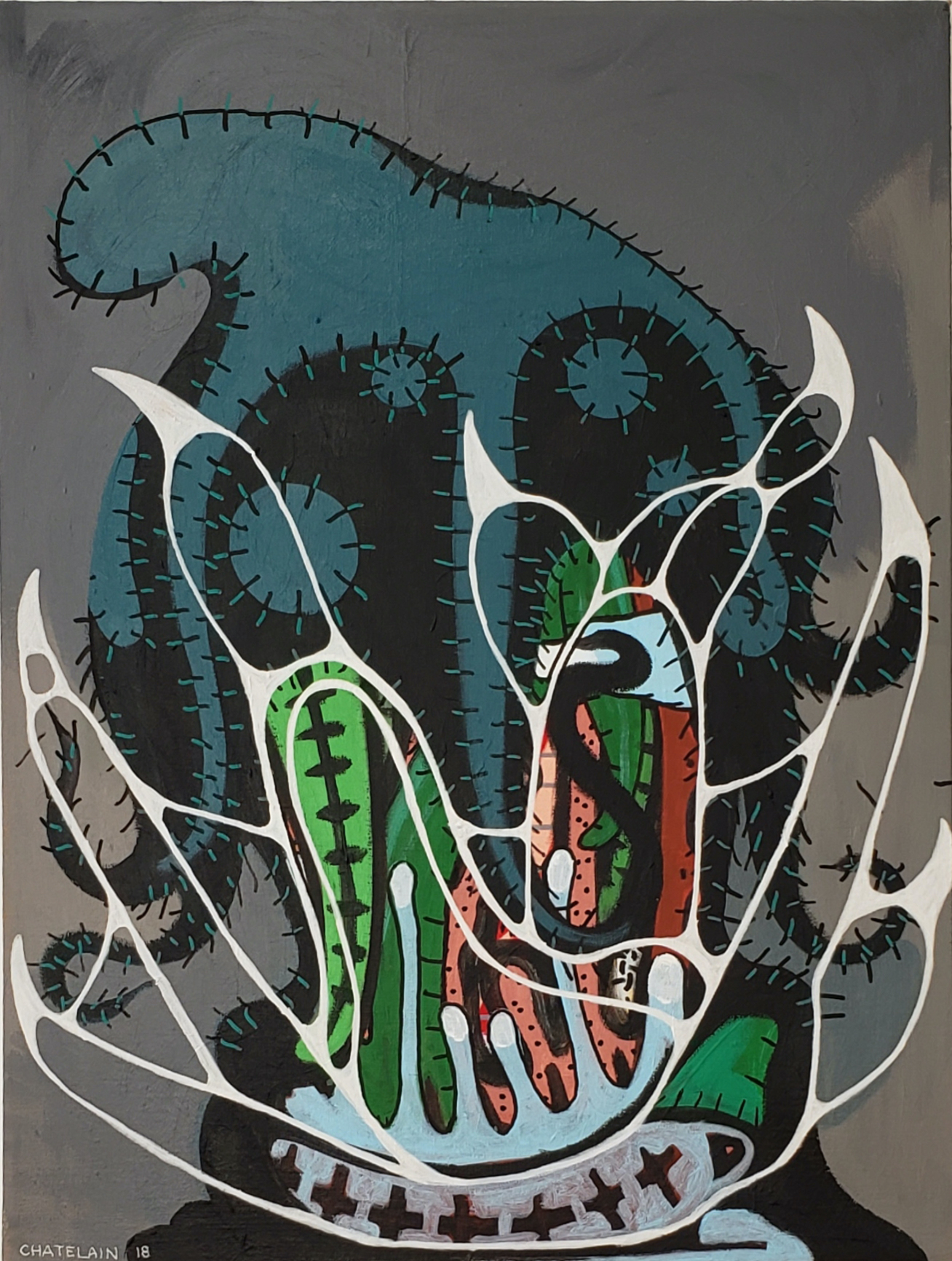

Mark Newport, Mend 21, Wool, acrylic, cotton, 40 x 28 in., 2021. Photo: George P. Perez

Mend 21 (2021), a prime example of one of Newport’s ongoing Mending series, began, like most, with a cut into the wool army blanket material, indicative of the inevitable tears and abrasions in a fabric used to warm and protect a vulnerable body. The subsequent mending of the cut, via darning and embroidery, leaves a physical reminder of the repair or “scab,” as per the artist. Executed with thick or thin thread, the circular or rectangular halos surrounding these wounds add subtle color and texture to the gray wool ground of the blanket.

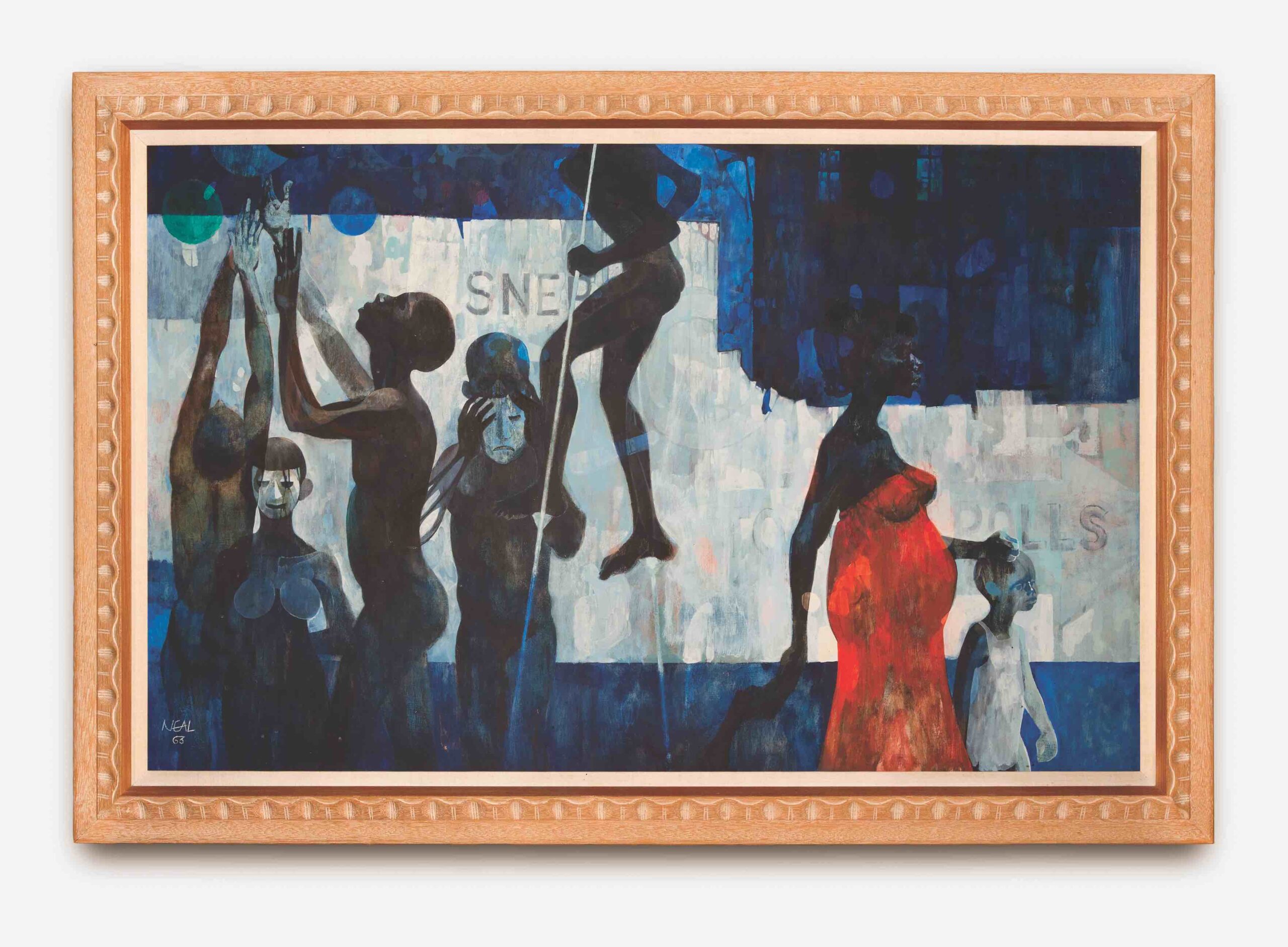

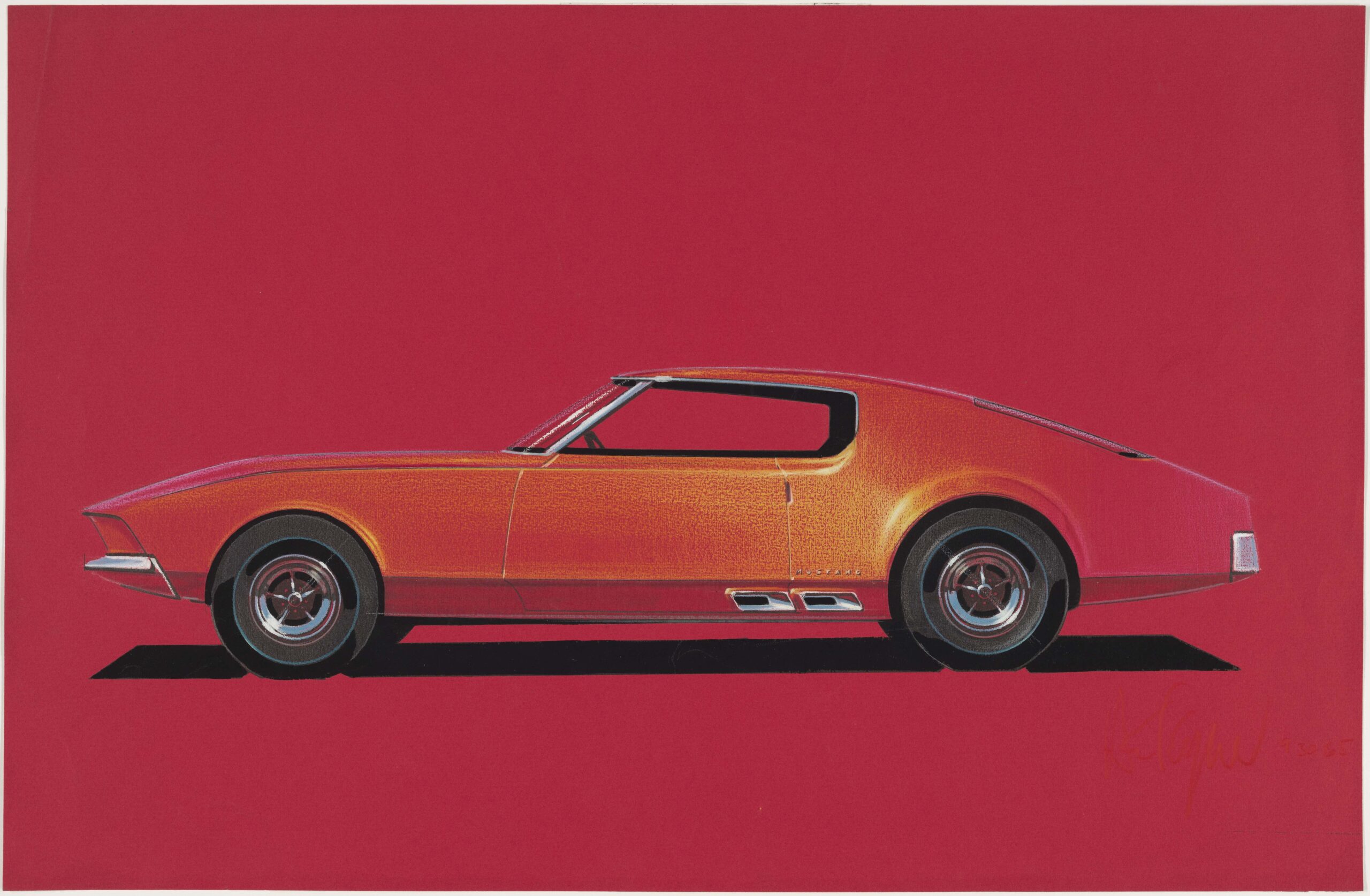

Mark Newport, Swathe, Wool, acrylic, cotton, 83 x 59 in., 2023. Photo: George P. Perez

Swathe (2023), the largest and one of the latest Newport works on view, is boldly and brazenly colorful, sporting three swaths of yellow at the left, a squiggly yellow line above, green, black, and brown horizontal stitching within two amoebic forms near the top, plus an organic oozing of multicolor hues at mid-center countered by a punchy red and black plaid patch at lower right. Moreover, the scrunched and bunched ball of fabric right of center heightens tactility and tautens Swathe’s irregular shape.

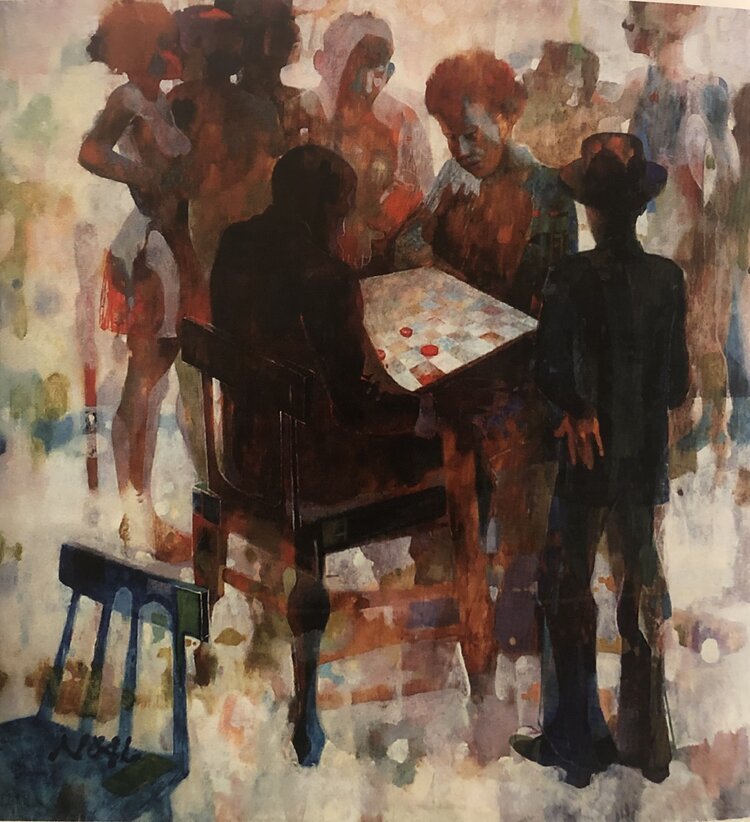

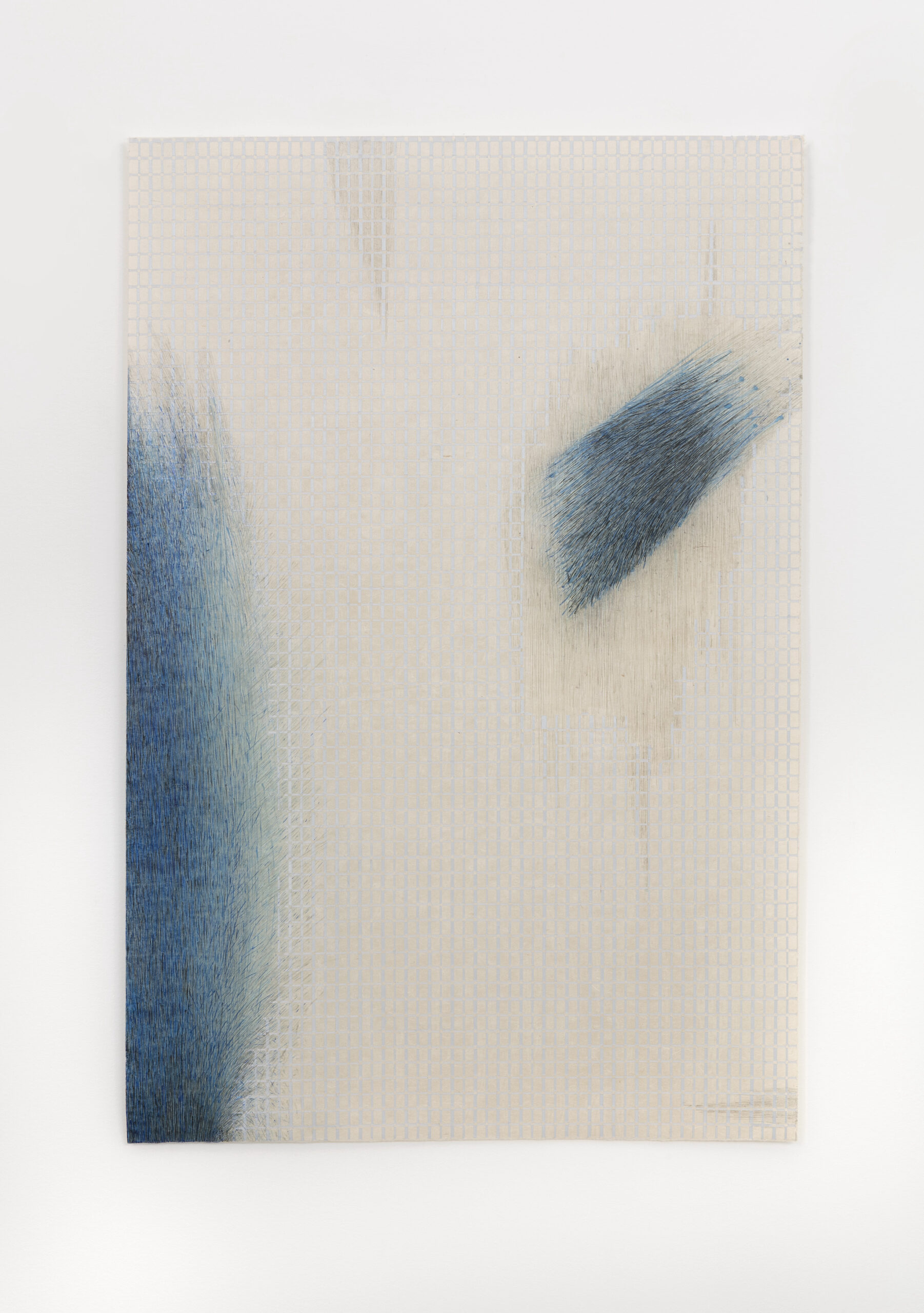

Jane Lackey, Almost being said, flow 3, Acrylic, ink, graphite, paper, 35 x 23 in., 2022. Photo: Addison Doty

Lackey’s Almost being said, flow 3 (2022), one of her identically titled drawings (with numerical designations), establishes the format for a quartet of spare, asymmetric arrangements of flowing cobalt forms encroaching upon precisely drawn paper grids. Like Newport, she too begins with consistent support, his an army blanket, hers a grid, that each artist then disrupts or interrupts. Here, in flow 3, two cobalt forms appear to be advancing toward the center, one on the left edging in slowly, the other at the upper right moving (hurtling?) comet-like toward the center. As Lackey’s lyrical titles imply, something undefined is being said, thought or felt, but provocatively, what that is, is only “almost” laid bare.

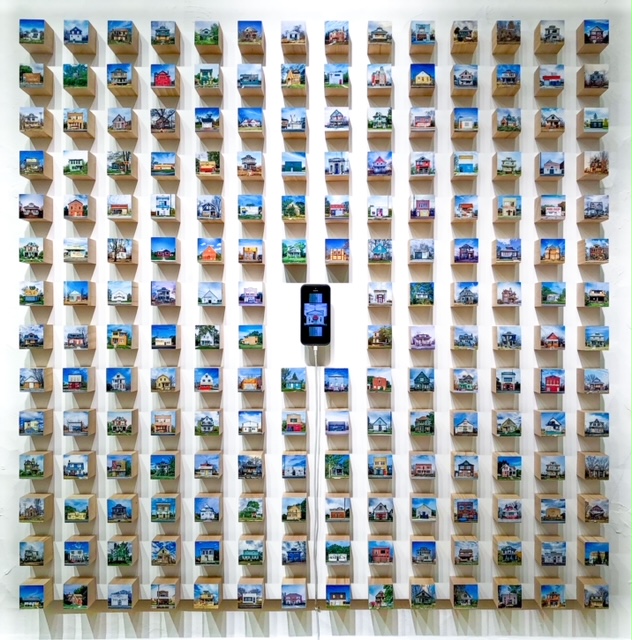

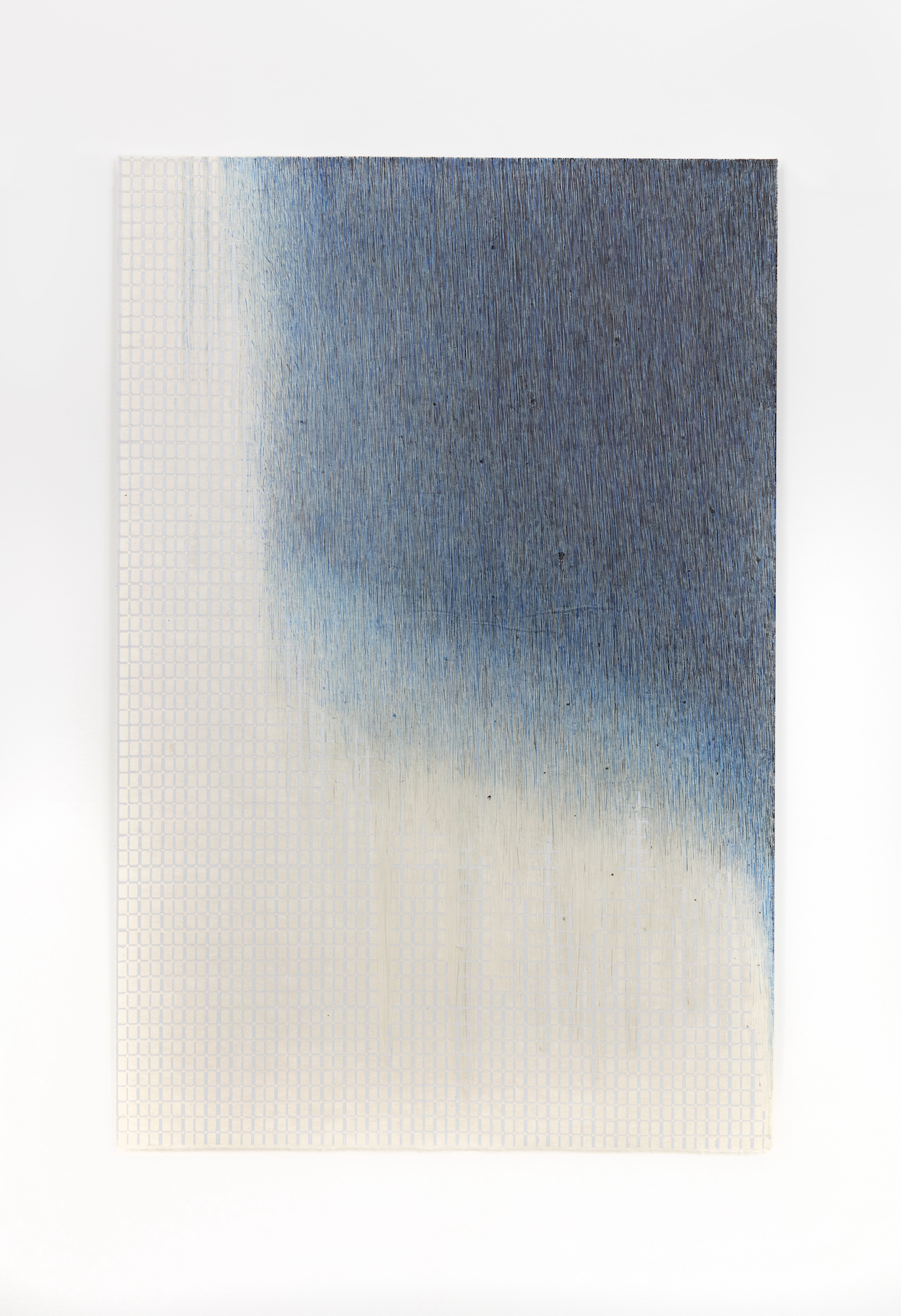

Jane Lackey, Almost being said, flow 4, Acrylic, ink, graphite, paper, 35 x 23 in., 2022. Photo: Addison Doty

Similarly, in Almost being said, flow 4 (2022), the slowly descending blue form appears to be on the verge of enveloping the tight, orderly grid. The tempo varies from composition to composition, evoking states of mind, emotional ups and downs, shifting moods and, as Lackey observes, “assertions of self within a plaid of connective tissue.”

Hence, Mark Newport and Jane Lackey: Together and apart, singular but connected, Midwesterner and Southwesterner, two makers linked across the miles via stitching and flowing. Correspondence, not competition, as they’ve confirmed, is the order of the day.

Correspondence is on view at Simone DeSousa Gallery, 444 W. Willis St., Detroit, MI, through August 12, 2023.