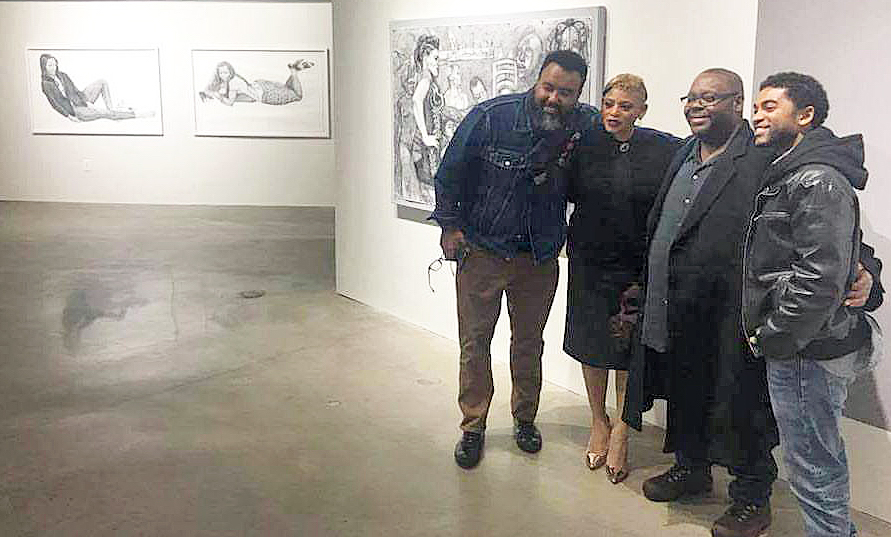

Flag of a Complicated Nation: Nabil Mousa’s Vision of the American Landscape at Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, MI

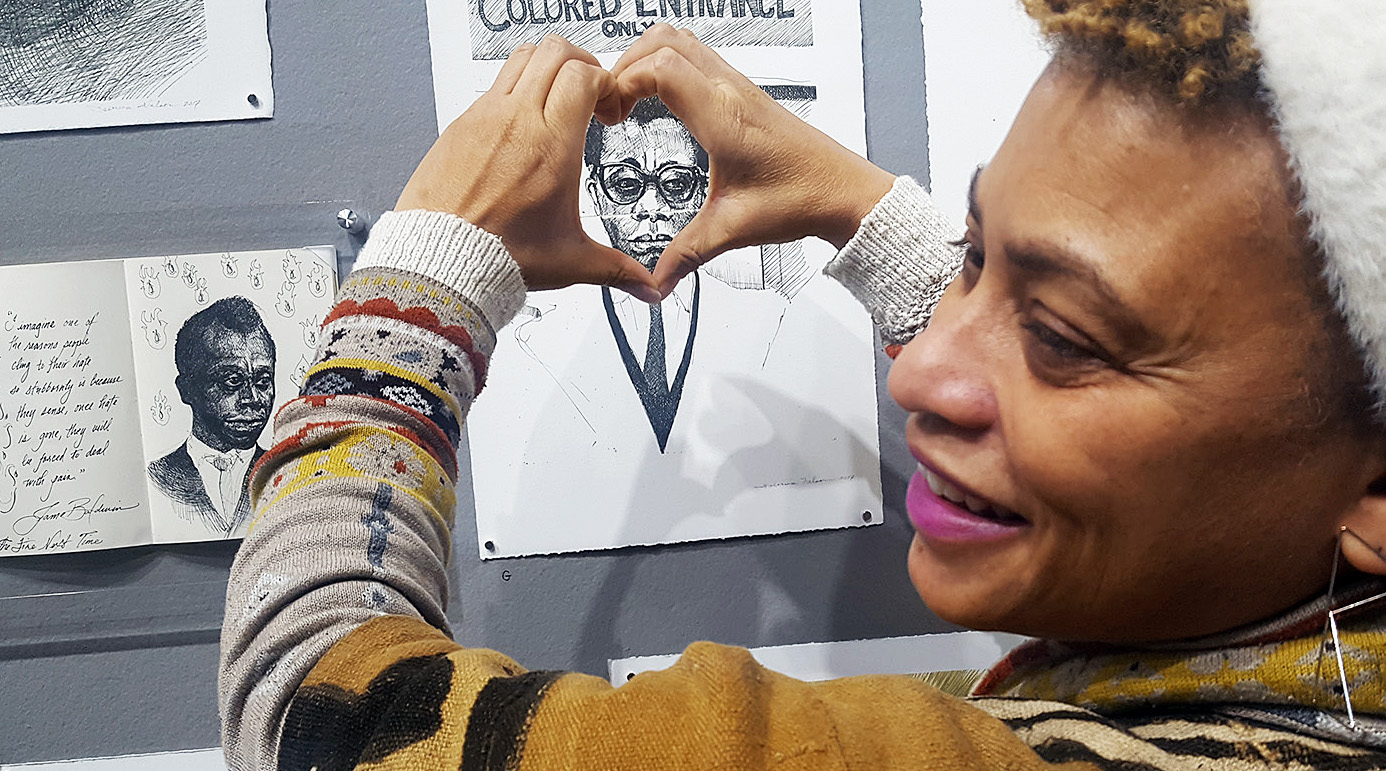

Image Courtesy of Artist

It is a complicated time in the United States, with polarizing politics pushing questions of what it means to identify as American. In truth, ideas of nationalism in most countries are increasingly complex, due to the up-tempo of immigration and displacement, and the generally more global nature of contemporary times. Flags, as a starkly graphic symbol of national identity, tend to fall short as representational entities for countries full of individuals with radically divergent backgrounds, experiences, and inter-cultural connections.

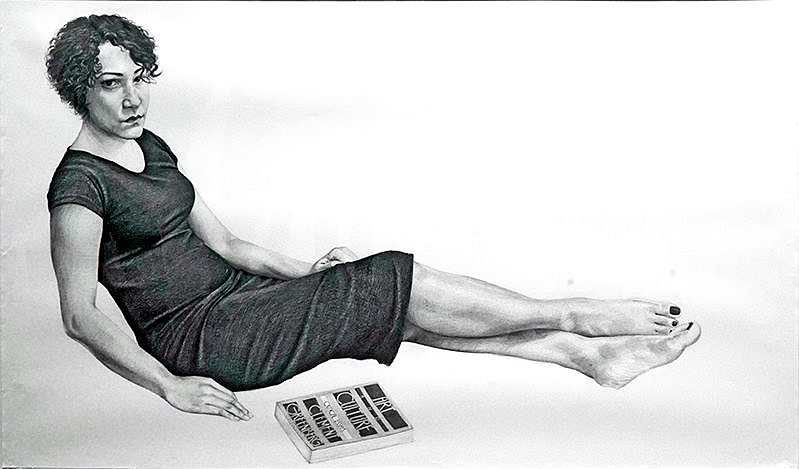

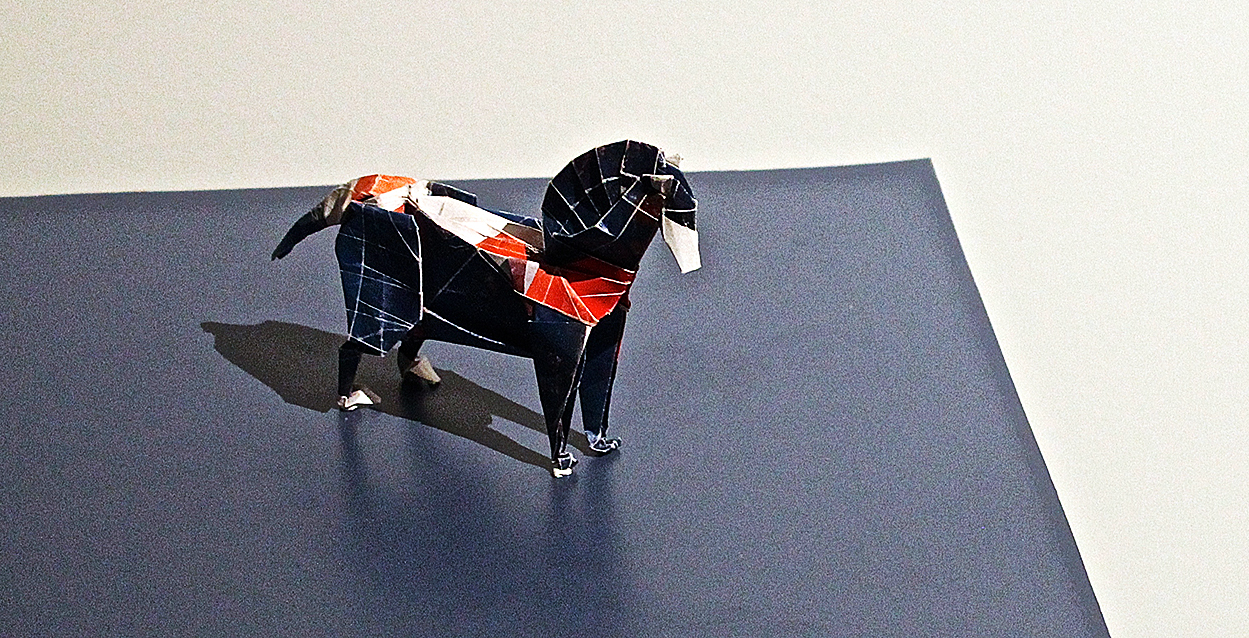

Nabil Mousa, American Landscape #38, Mixed Media on board, 24 x 96″, 2008

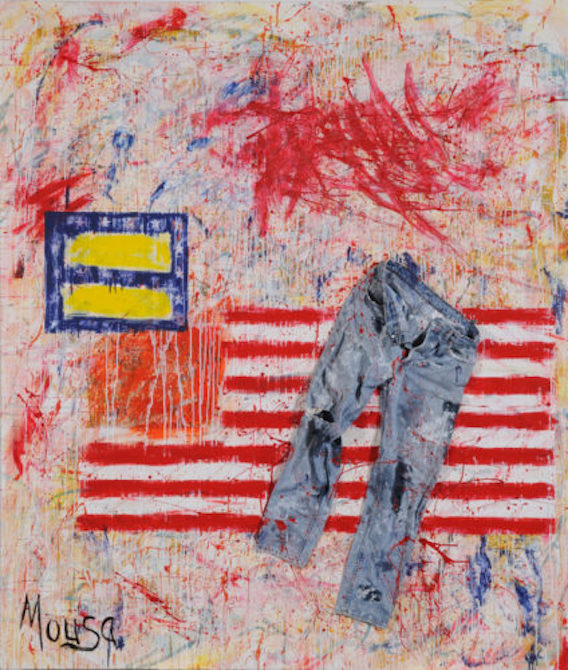

Perhaps this is why Nabil Mousa’s, American Landscape—a series that includes some 40 works produced by the artist between 2008 and 2012—feels so timely and resonant. Nine of these works are on display at the Arab American National Museum, and most of them incorporate the American flag, as a literal or symbolic material. The series is a way for the artist to reconcile his own questions of identity, both as a Syrian immigrant and an openly homosexual man. Mousa came to the States with his family in 1976, at the age of 12, and since coming out as gay, has been estranged by his family, according to their stringently Christian beliefs. It stands to reason that the flags he presents are emotional, messy affairs, with blurring lines, dramatic brushstrokes, mottled palette, and populated by little icons representing anonymous men and women of the LBGTQ+ community.

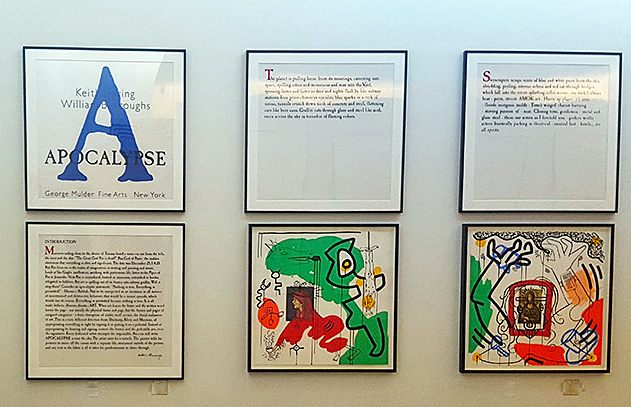

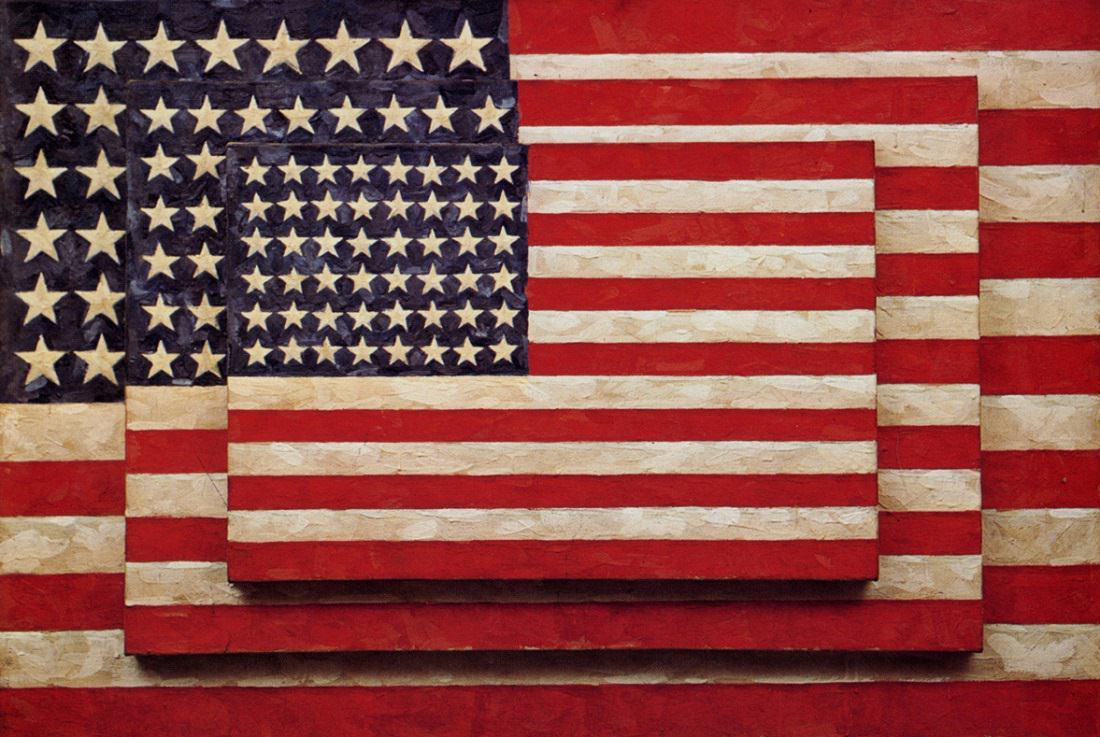

Jasper Johns, Three Flags, 77 x 155cm, Pigment & Warm wax, Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum

Flags in general, and the United States flag in particular, have a long history of use in contemporary are for their symbolic value. Jasper Johns first began to iterate the symbol with the encaustic painting Flag (1954-55), following his discharge from the United States Army, and returned to the flag as subject matter numerous times over the course of his career. Political artist Dread Scott first presented his controversial work, What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag? In 1989, prompting the passing of the “Flag Protection Act” in Congress. In protest, Dread Scott and two other artists burned a U.S. flag on the steps of the Capitol Building, which resulted in a federal court case that made it all the way to the Supreme Court in 1990. Artist David Hammons famously created the African American Flag, which is in the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art. Flags provide pre-loaded symbolism, and evoke strong feelings in those that choose to identify with them as a form of national identity, thus making them appealing to artists who question where they may fit in with such broad social representations.

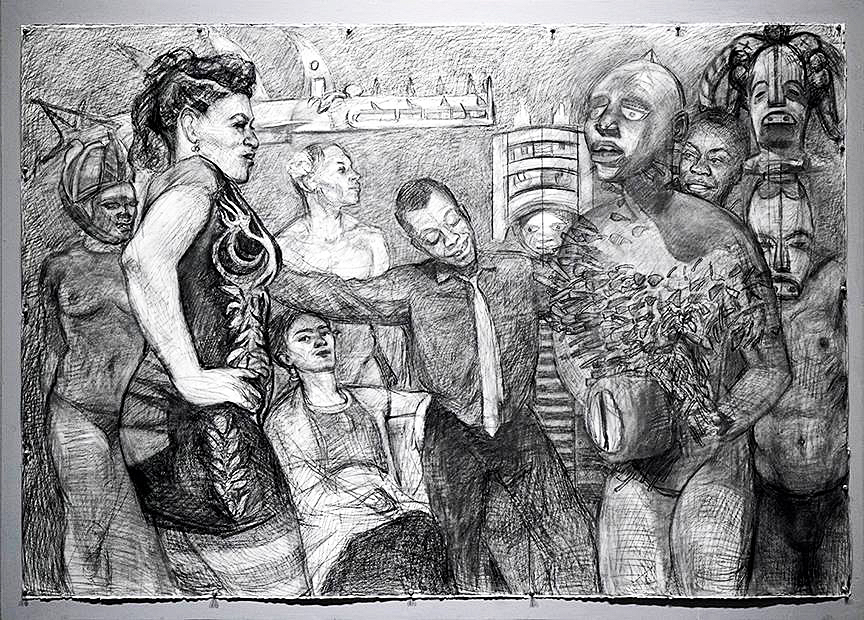

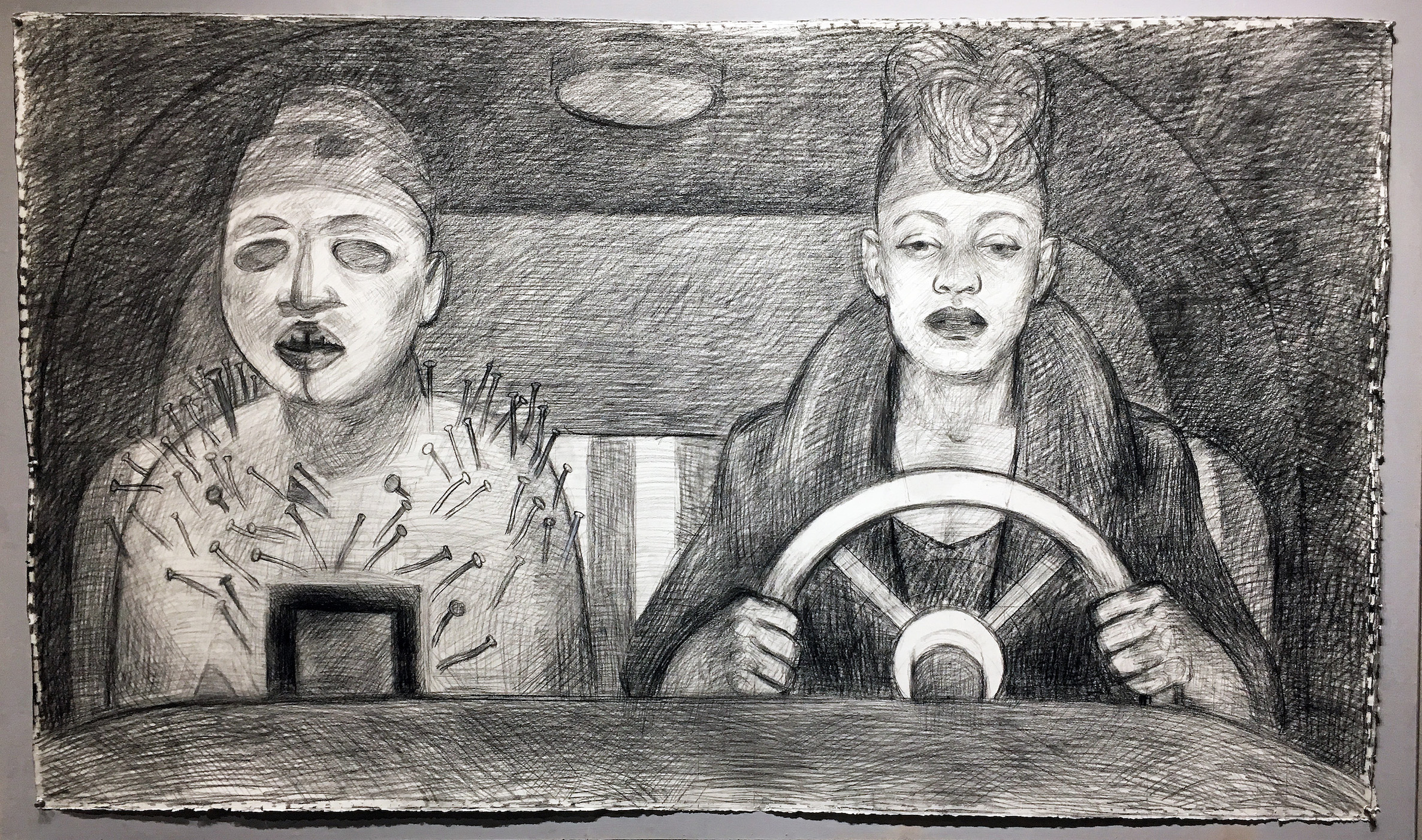

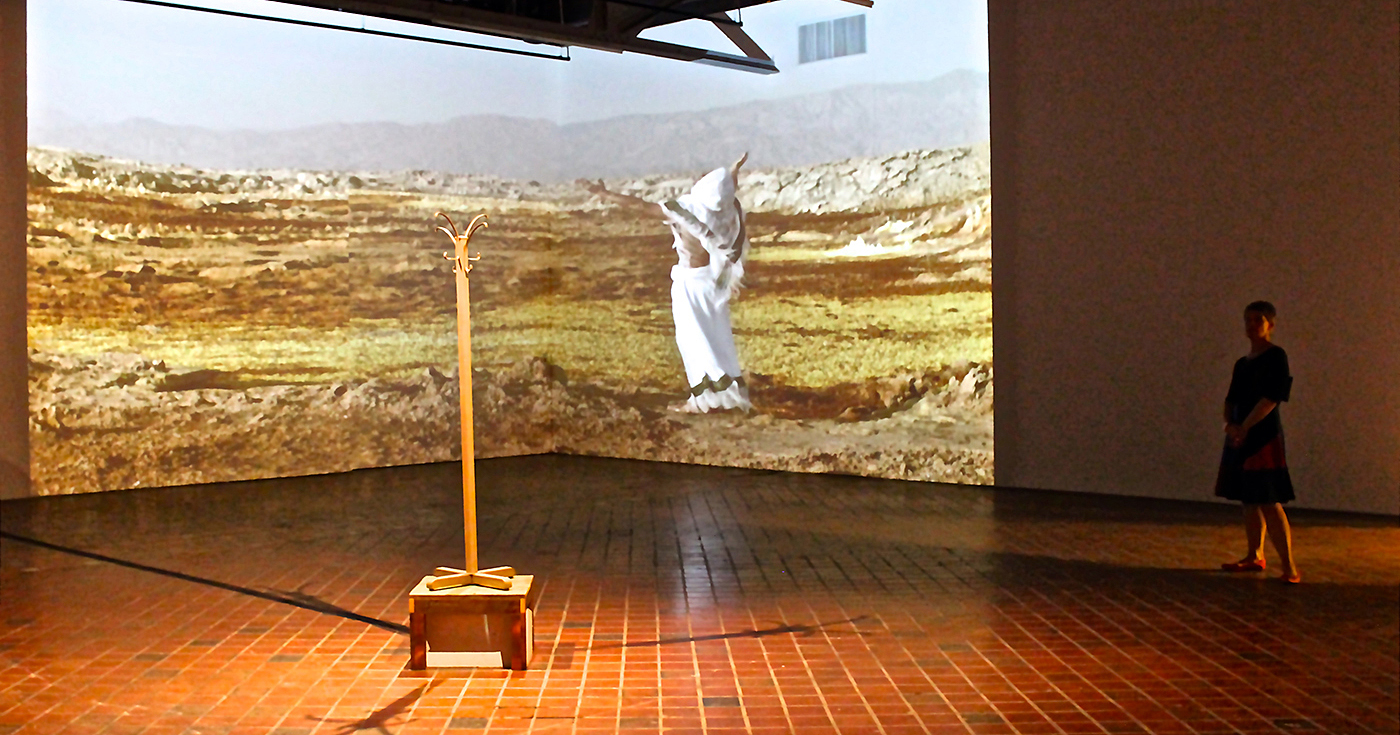

Nabil Mousa, American Landscape, # 34, Mixed Media on oil board, 48 x 48″, 2009

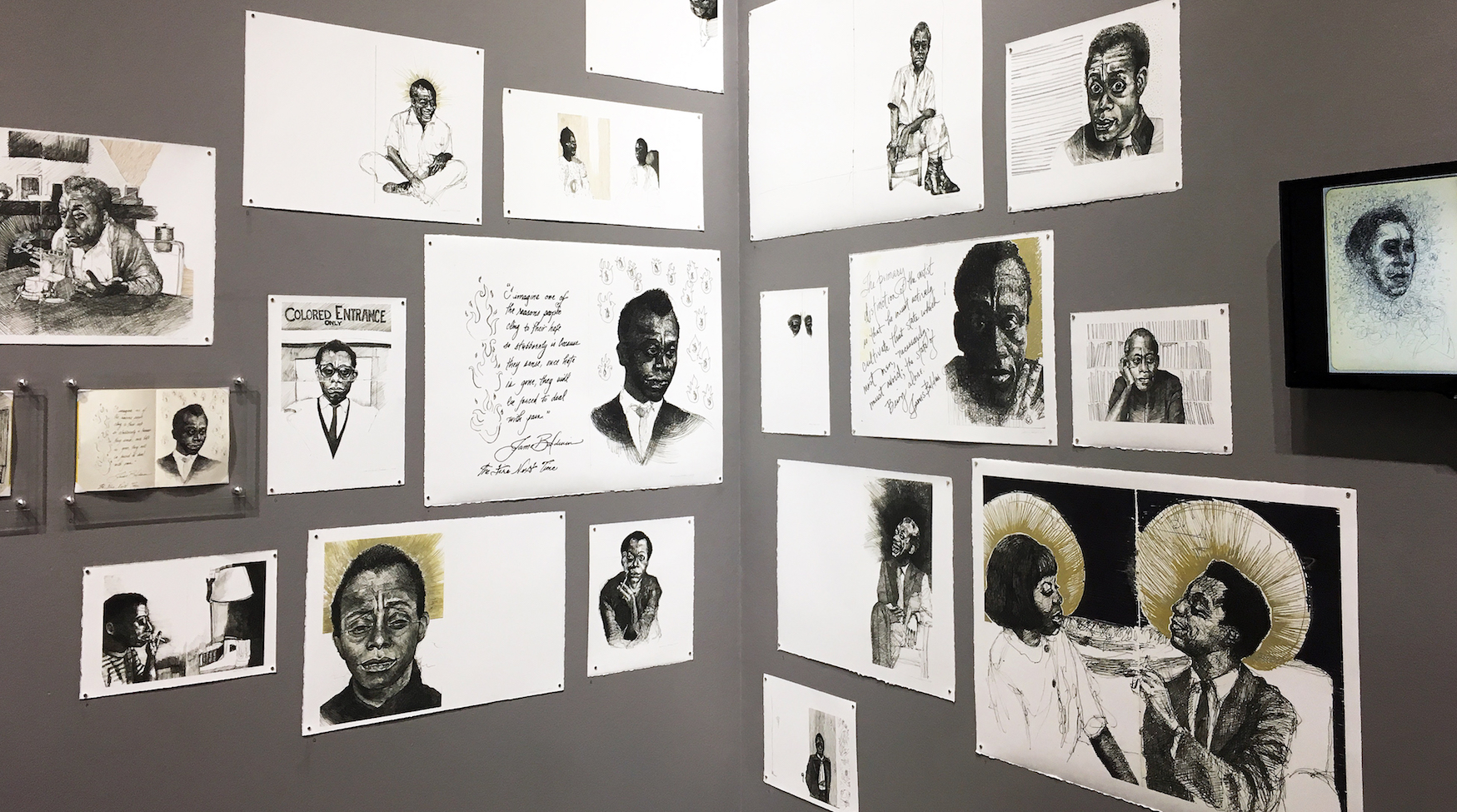

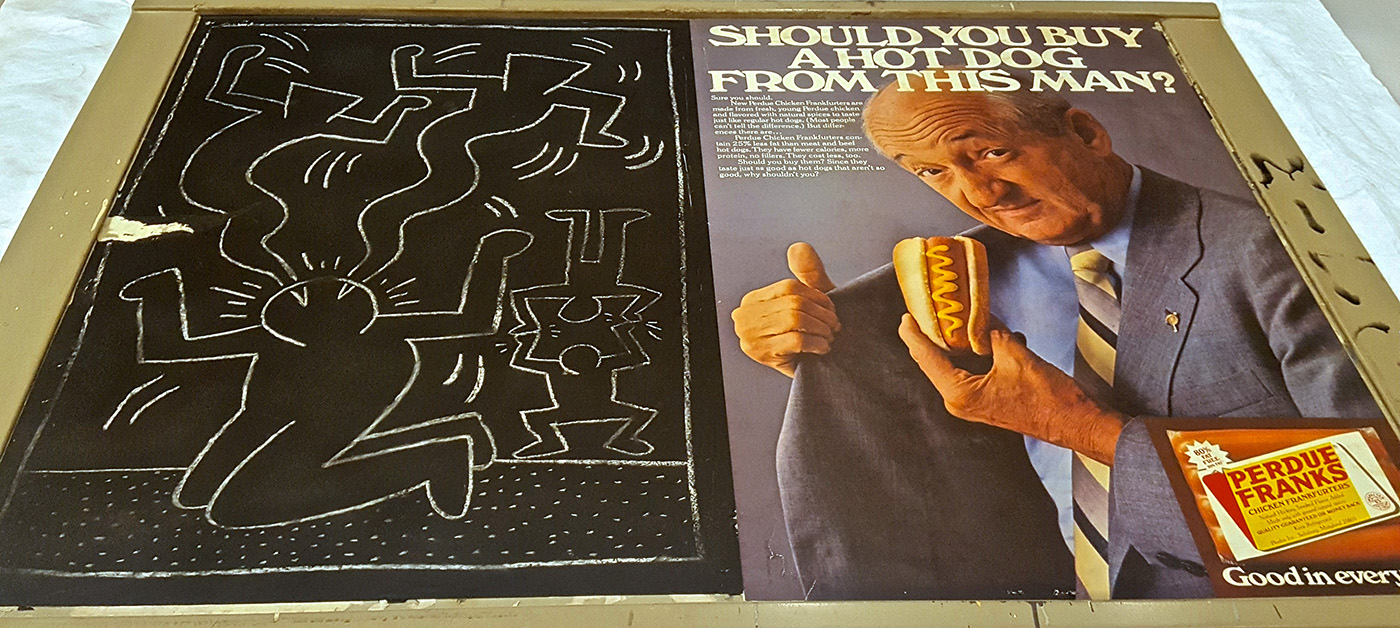

As a member of (at least) two populations that are often vilified, singled out, or marginalized, Mousa has a great deal of personal experience in alienated nationalism to work through in his paintings, yet with American Landscape, he has chosen to present these themes using some of the most universal symbols available—aside from the flag, the majority of figures in Mousa’s landscapes are the male/female icons designating gender on public restroom doors. In Mousa’s context, these figures appear exclusively in same-sex couplings or groups; four women holding hands across an apocalyptic and bleak multi-media landscape in American Landscape #34 (2009), or dozens of men holding hands in rows that fill out the stripes of a 12-foot-wide American Landscape #1 (2009), which dominates the entire entry wall of the gallery, and, as the largest work, serves as the focal point of the exhibition. The figures seem to blend with flag behind them, suggesting their invisibility, and in many of Mousa’s works, the flags themselves smear and drip, or even fragment—as in the case of American Landscape #19 (2009), which incorporates cut-up pieces of an actual U.S. flag in the foreground, obscuring portions of the large-scale male figures in the painting, including the place where they are (presumably) holding hands.

Nabil Mousa, American Landscape #1, Oil on Board, 90 x 144″, 2009

In some ways, Mousa’s work at AANM might be trading in the bluntest symbolism, but the emotive nature of his brushstrokes and the frenetic energy of such bold and colorful works in a relatively small gallery space make the work personal and the exhibition space feel extremely dynamic. Perhaps this is a show that seeks to connect with those who feel excluded by the conventional presentation of the flag, which blithely assumes a one-for-all American spirit that is obviously not borne out in issues of policy-making, opportunities, justice, or social equity. With American Landscape, Mousa has complicated the flag, and in doing so, raised a new version, which seeks to include people whose American identities are more complicated than simple red, white, and blue.

Nabil Mousa, American Landscape, #20, Mixed Media on Board, 96 x 72, 2009

Nabil Mousa: American Landscape continues at the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan through April 8.