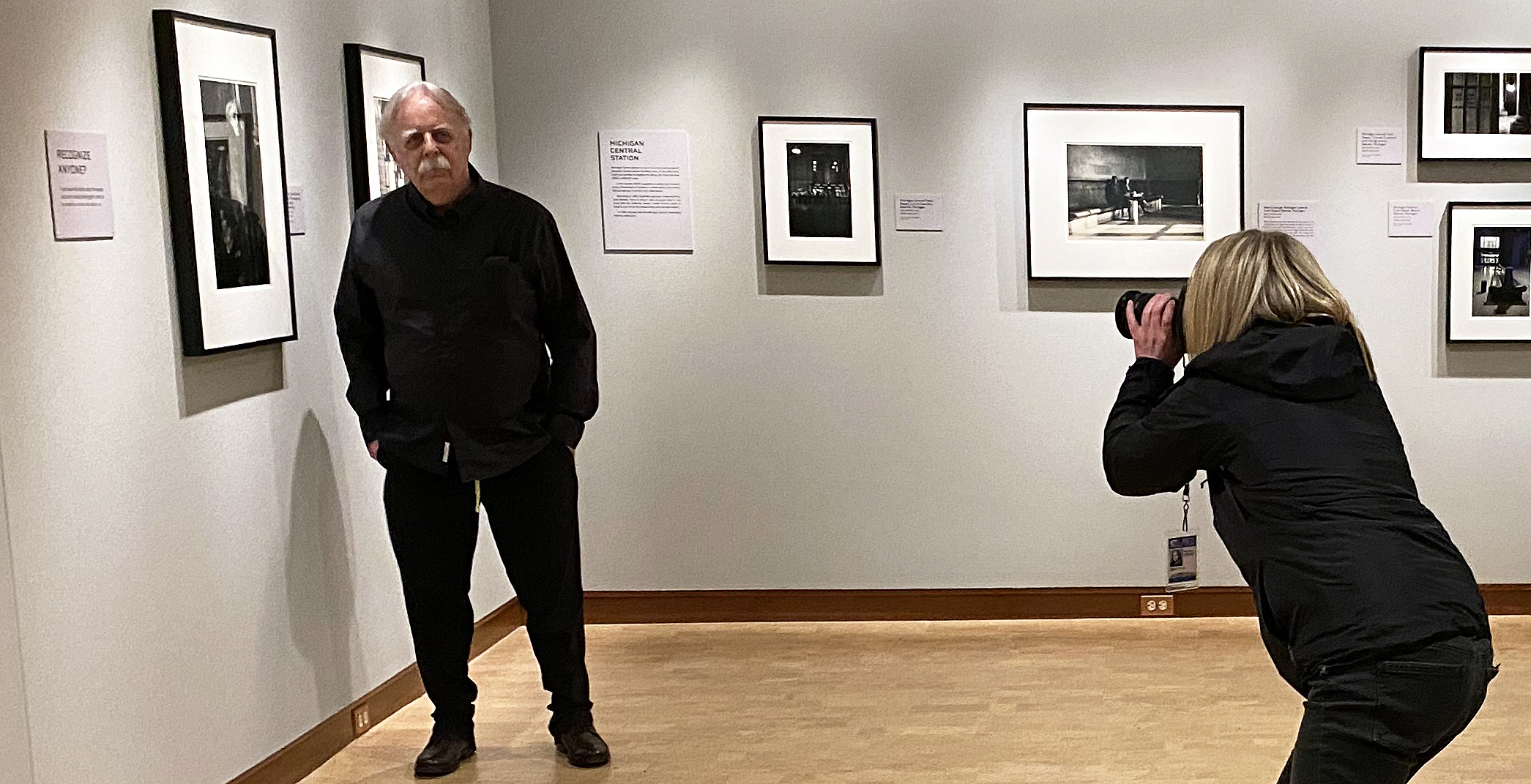

The James Pearson Duffy Department of Art and Art History, Wayne State University, presents the 2020 WSU Faculty Exhibition, a virtual exhibition that opened November 19, 2020.

The Art Department Faculty Exhibition at Wayne State University began as an installation in the Community Arts Gallery but quickly became virtual in mid-November 2020 to conform with university Covid-19 requirements. Faculty members from the department who advance the study and practice of art history, design and fine art come together to reflect the university’s full spectrum of area disciplines. Click on this link, and you’ll find these images above are links to each faculty member’s work here: https://www.waynestategalleries.org/2020-faculty-exhibition-2

Adrian Hatfield, If this isn’t nice, what is?, 2019 oil and acrylic on canvas 48” x 36”

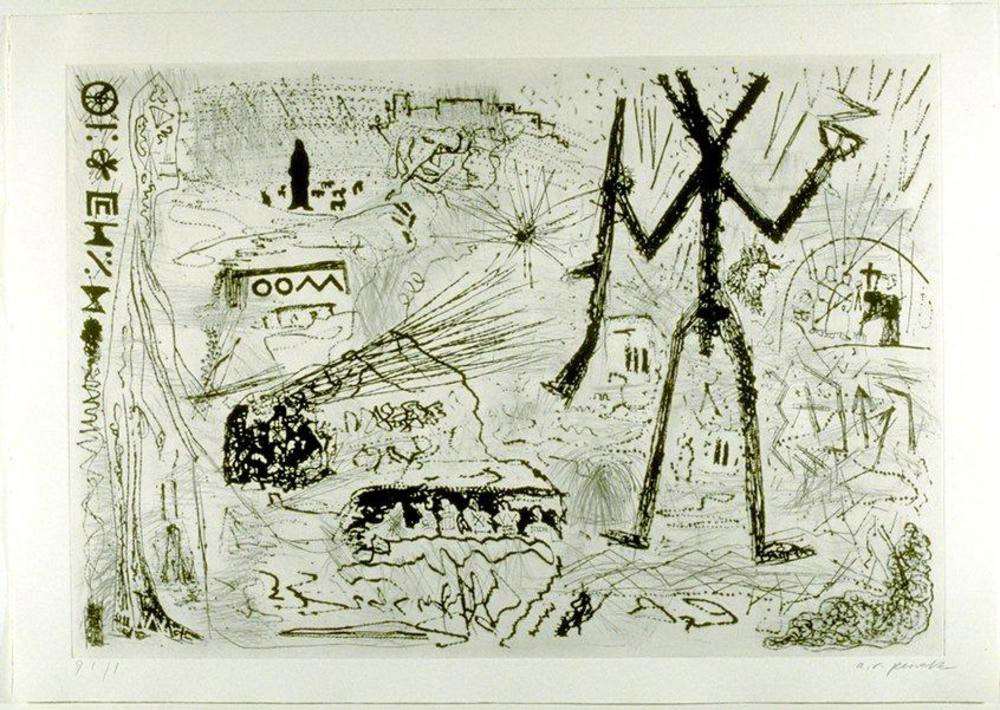

The painting and sculpture of Adrian Hatfield remind this writer of the term magical realism, more often referred to in literature, but that may apply here. The term magical realism was introduced by Franz Roh, a German art critic in 1925. When Roh coined the term, he meant it to create an art category that strayed from the strict guidelines of realism, which Hatfield’s collage-like work conveys. Hatfield’s work recombines art historical imagery from the industrial revolution and the Romantic era with imagery from current and environmental concerns. In the work, he creates a black & white drawn universe, juxtaposed to these full colored floating dimensional shapes and landscape, part of a dualism that plays with the viewer’s process.

In his statement, he says, “As I explore this dualistic theme through the remodeling of art-historical and scientific imagery, the resultant pieces are mournful, unnerving, and yet oddly hopeful.” Adrian Clark Hatfield earned his B.F.A. from Ohio State University and his M.F.A. from Ohio University. https://www.adrianhatfield.com/

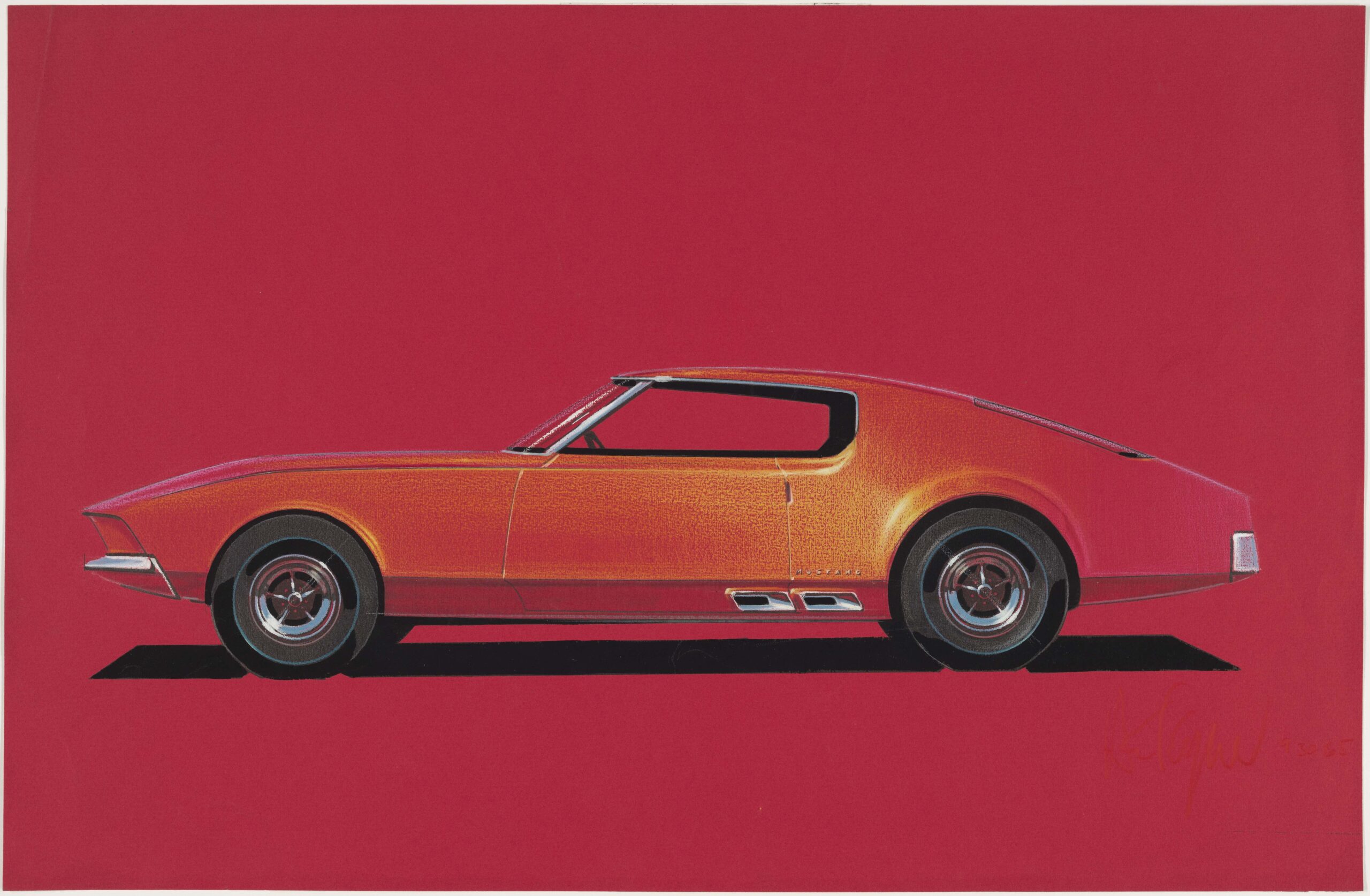

Margi Weir, Caution Guardrail, 2020 India ink, Sumi ink, watercolor

Patterns are a large dominating part of Margi Weir’s oeuvre, as illustrated here in this work, Caution Guard Rail, 2020. She uses this technique she describes as Snap Line when she dips cotton twine into thinned acrylic paint or ink and snaps a taut line onto a supporting surface. The spray from the line often begins the process for the composition. Weir’s body of work is expansive and includes paintings, drawings, prints, and installations. The paintings and prints are dominated by a highly developed geometric and colorful pattern. There is a theme reflected somewhere in the pattern, often in the border, where she stitches together multiple symbols to make them visually appealing.

She says in her statement, “In one body of my work, I use a computer (a non-traditional painter’s tool) to repeat images that I stitch together visually in order to make an appealing pattern, often resulting in tapestry-like, spatially flattened compositions. This references pre-Renaissance and/or non-western methods of pictorial organization, for storytelling purposes, that were used in textiles, ceramics, and architectural decoration. This particular use of juxtaposed images, stacked and repeated, is a unique addition to the visual language of painting in the 21st century.”

Ms. Weir earned her MFA in painting from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA); her MA in painting from New Mexico State University. She also holds a BFA in painting from San Francisco Art Institute and BA in art history from Wheaton College. https://margiweir.weebly.com/

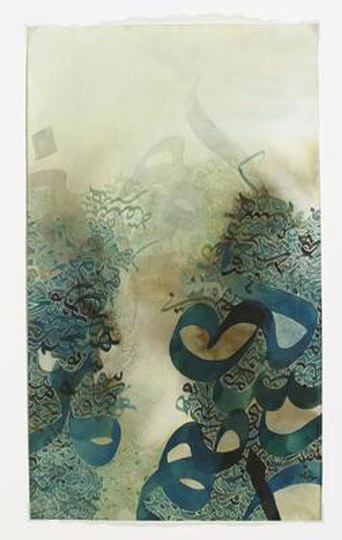

Millee Tibbs, Transfrontalier, 2018 Gelatin Silver Print + Custom Frame

To describe Millee Tibbs’s work as landscape photography would not be complete, although she is using a camera and capturing images of mountainous terrain. Instead, that would be the starting point for various manipulations; whether it be the entire shape of the image or the overlay of a second geometric shape on the terrain, there is an astute variety in how these images are presented. The artwork derives from Tibbs’s interest in photography’s ubiquity and the tension inherent in manipulating reality. Sometimes it is in the overlay of a geometric shape on the mountainside; other times it includes the shape of the image, mat, and frame. It’s as if the mountain terrain becomes the backdrop for an artist interested in what I might call a shaped canvas work: Frank Stella, 1965; Ellsworth Kelly, 1970, or Elizabeth Murray, 2006.

She says in her statement, “My work has evolved into an investigation of idealized landscape imagery – the kind that is easily consumable and often commodified. I am fascinated with the landscape genre and its language, the aesthetic imposed onto the land through photographic framing, and the historical rhetoric inherent in these images that justified Manifest Destiny and conquest through what is left out—namely inhabitants.”

Millee Tibbs earned her B.A. from Vassar College and her M.F.A. from Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) https://www.milleetibbs.com/

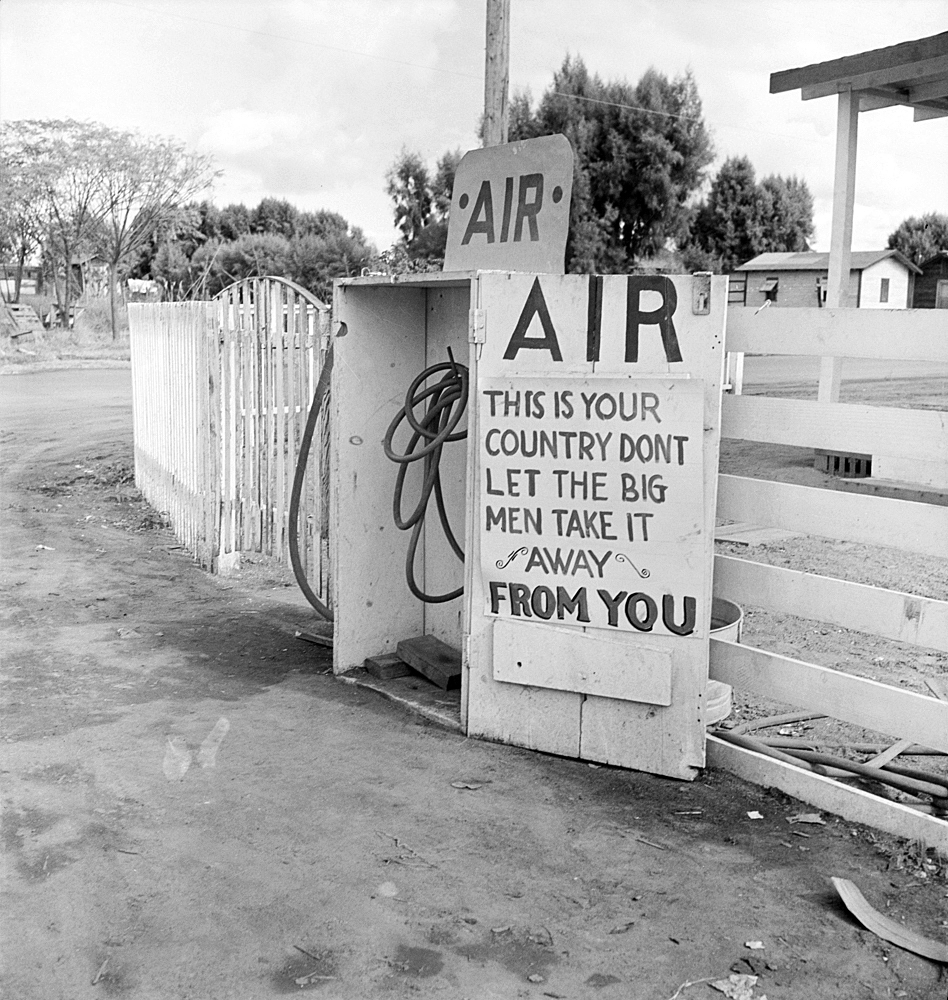

Sheryl Oring, “I Wish to Say” Video, 5:13 minutes

The video work of Sherl Oring investigates social issues through projects that incorporate on-camera interviews that examine public opinion. In “I Wish to Say”, Oring sets up a portable office where woman in secretarial costume interview individuals at large about the state-0f-affairs in the U.S. and documents their comments using a typewriter, intending to main a postcard to the White House. To date, nearly 4000 postcards were mailed.

Having worked in educational television, it is important to say the standards and caliber of production in these short videos are of the highest quality: the recording of imagery and audio and the direction and editing of these videos are highly produced. The “I Wish to Say” project has a companion book from the University of Chicago Press, Activating Democracy, a result of helping people from across the United States voice their political concerns.

From the Public Art Review, “Sheryl Oring’s multiyear, ongoing I Wish to Say project—in which she sets up a desk with a typewriter and invites people to dictate a letter to the President or a presidential candidate, which she types and sends—is a catalyst for a deeper look at artists’ intersection with public policy.”

Sheryl A. Oring earned her B.S. in Journalism at the University of Colorado and her M.F.A. from the University of California. http://www.sheryloring.org/

Works by the following full and part-time faculty are featured in the exhibition: Maria Bologna, Kiley Brandt, Betty Brownlee, Allana Clarke, Pamela DeLaura, Jessika Edgar, Laura Foxman, David Stephan Graves, Richard Haley, Adrian Hatfield, Margaret Hull, Lauren Kalman, Deborah Kingery, Ruth Koelewyn, Brian Kritzman, Claas Kuhnen, Evan Larson-Voltz, Heather Macali, Katie MacDonald, Heather Mawson, Judith A. Moldenhauer, Carole Morisseau, Sheryl Oring, Kathyrose Pizzo, Tom Pyrzewski, Kyle Sharkey, Rebekah Sweda, Andrea Thurston-Shaine, Millee Tibbs, Maureen Vachon, Margi Weir, and Golsa Yaghoobi.

Wayne State University, 2020 Faculty Exhibition, a virtual exhibition opened November 19, 2020, and runs through January 8, 2021.