William Anders, Earthrise, 1968. Courtesy NASA.

A Brief History of Art in Space is a rewarding exhibit at the Broad, East Lansing, occasioned by the 50th anniversary of the auspicious moment when the Eagle, the Apollo 11 lander module, successfully made touchdown on the surface of the moon. Though the Apollo space missions were for space exploration, their influence resonated in profound and unexpected ways back on earth. This exhibit is small, but the works included (such as the famous 1968 Earthrise photograph captured by William Anders) are freighted with real significance, and, in their ability to make us pause and think about the cosmos and our place in it, they certainly verge into the realm of the sublime.

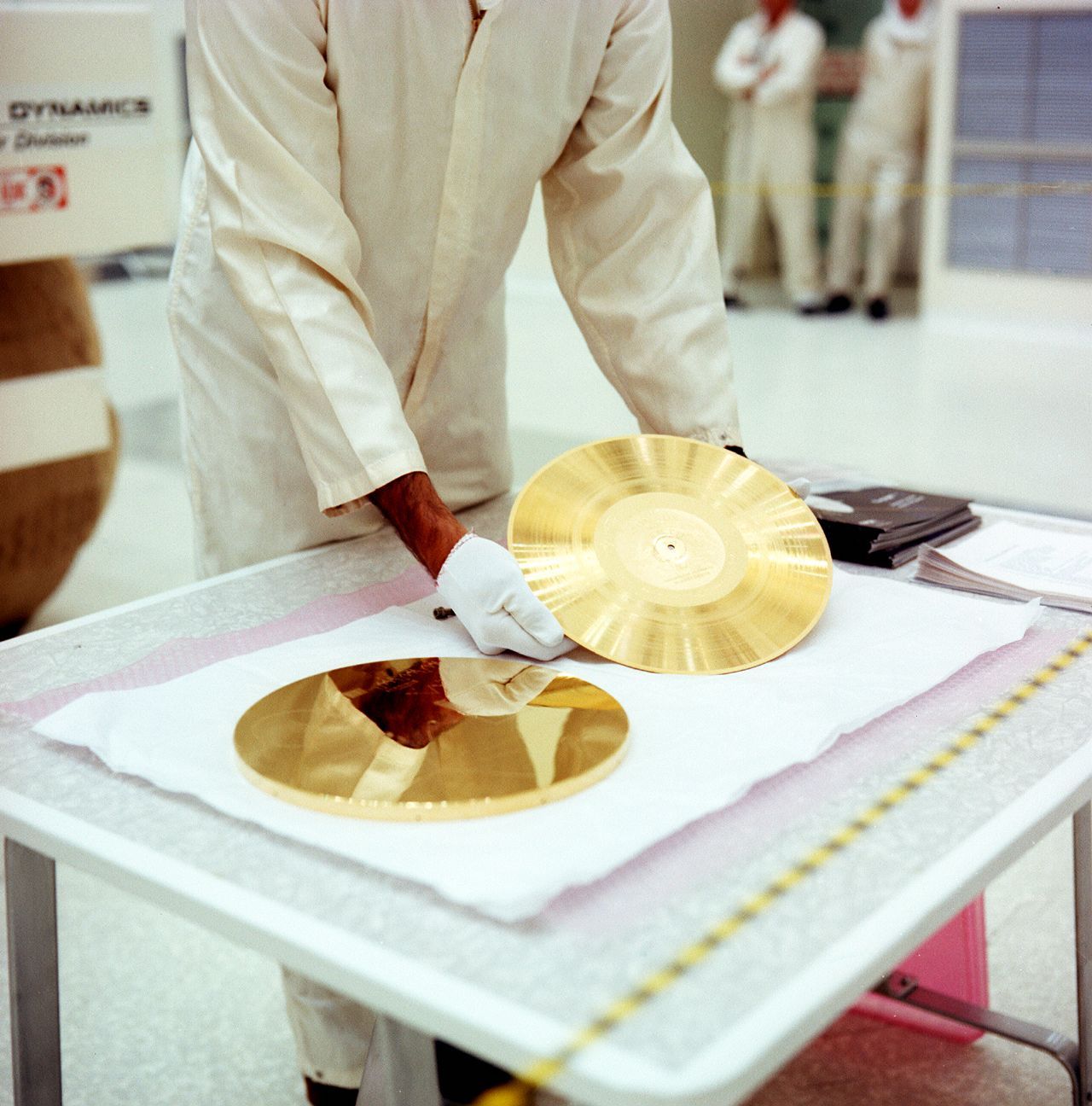

The exhibit comprises mostly NASA photography, though two headphones also allow viewers the chance to listen to the soundtrack of the Voyager Golden Record which was launched into space aboard Voyager I in the playfully optimistic hope that, should advanced life forms ever intercept the spacecraft, they could treat themselves to a sort of musical soundtrack of humanity (while NASA didn’t include an actual record player aboard the Voyager, it did thoughtfully provide an illustrative guide for how to make one).

Golden Record and Disc, 1977. Courtesy NASA.

Anders’ Earthrise is the star of this little show. Taken while Apollo 8 was in lunar orbit on Christmas Eve, 1968, the image juxtaposes the barren gray of the Moon’s pox-marked surface with the vibrant blues, greens, and whites of the distant earth. Lauded in Life magazine’s 100 Photos that Changed the World, the image helped garner substantial support for the environmental movement. There are other lesser-known photographs from other Apollo missions on view, an image of an astronauts boot-print in the moon’s dust, for example– an image charged with symbolism. These photographs, while originally taken for scientific purposes, are presented here for their merits as works of art rather than simply documentation.

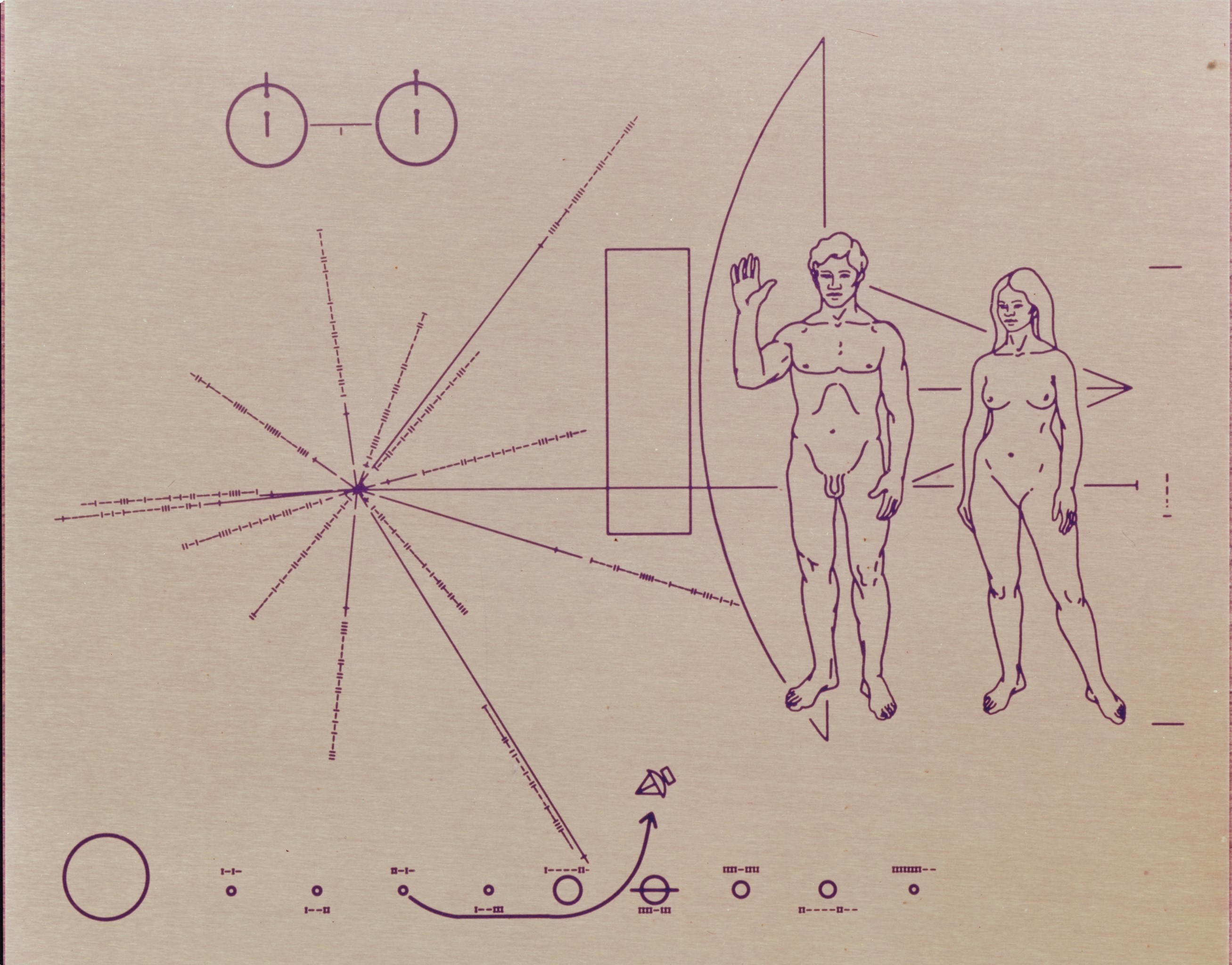

In addition to photography from the Apollo missions, the exhibit also highlights works of art that are in space, and it turns out there’s a small handful of art-objects either in orbit or making interstellar journeys. The best known is certainly the famous Pioneer Plaque designed jointly by Carl Sagan, Linda Salzman Sagan, and Mike Drake, attached to the exterior of Pioneer 10. In addition to a planetary map locating earth, the plaque also includes images of a nude male and female, each of which betray the influence of idealized classical Greek sculpture and Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man. Any extraterrestrial that actually views this plaque will see a comparatively air-brushed and tactfully censored portrayal of humanity and likely wonder why the female of the species lacks any genitalia. It’s subtle unintentional commentary on reality vs. art.

Pioneer Plaque, 1972. Courtesy NASA.

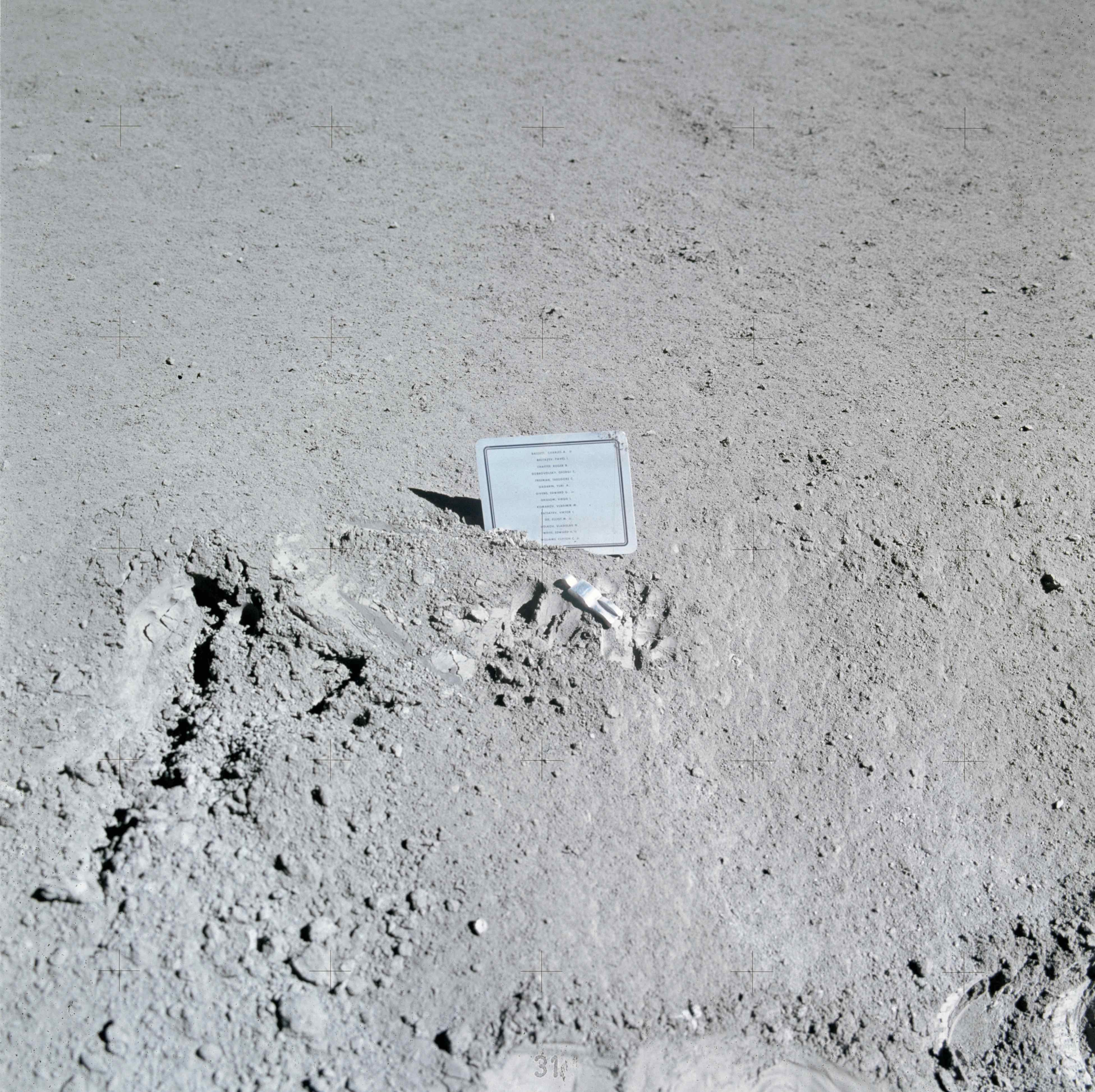

Also on view is a photograph from the Apollo 15 lunar mission, during which the astronauts movingly deposited a small abstract sculpture onto the moon’s surface along with a plaque containing the names of 14 American and Russian astronauts who had lost their lives on various missions. It was never an official part of the mission, so the sculpture, an intentionally genderless figure in a spacesuit, had to be smuggled aboard surreptitiously.

Apollo 15 crew, Untitled, 1971. Courtesy NASA.

Adjacent to the Vitrine gallery, the Broad’s Collection Gallery currently features an eclectic arrangement of photography which addresses the camera’s ability to capture a moment in time, in effect stopping the world, at least on a photographic print. The show, Nature Morte (“dead nature,” a French term generally reserved for still-life painting), takes its starting point from Susan Sontang’s observation that there’s a curious language of violence we employ to talk about photography, as when we “shoot” a picture.

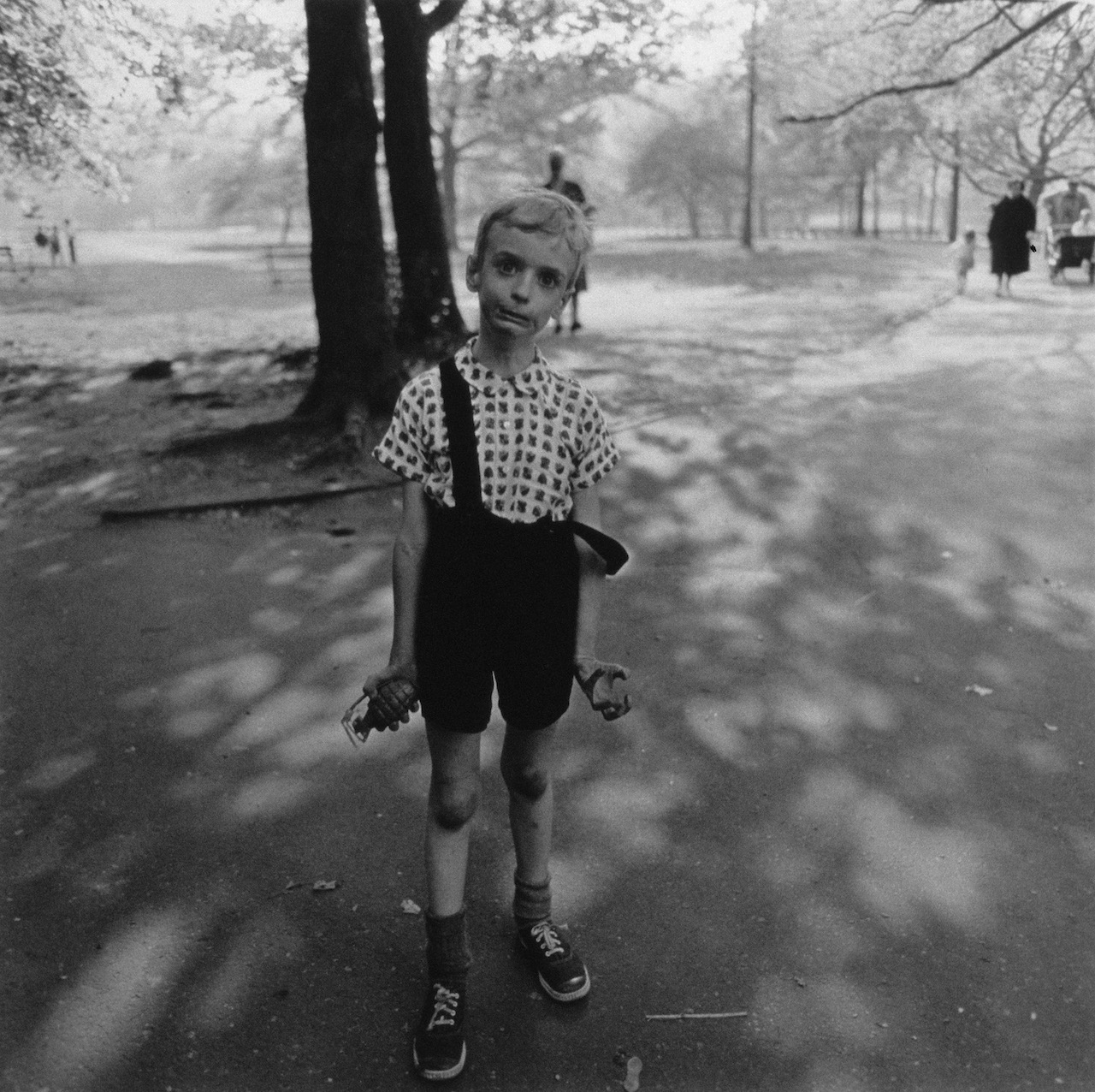

Diane Arbus, Child with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, New York City, 1962. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, purchase.

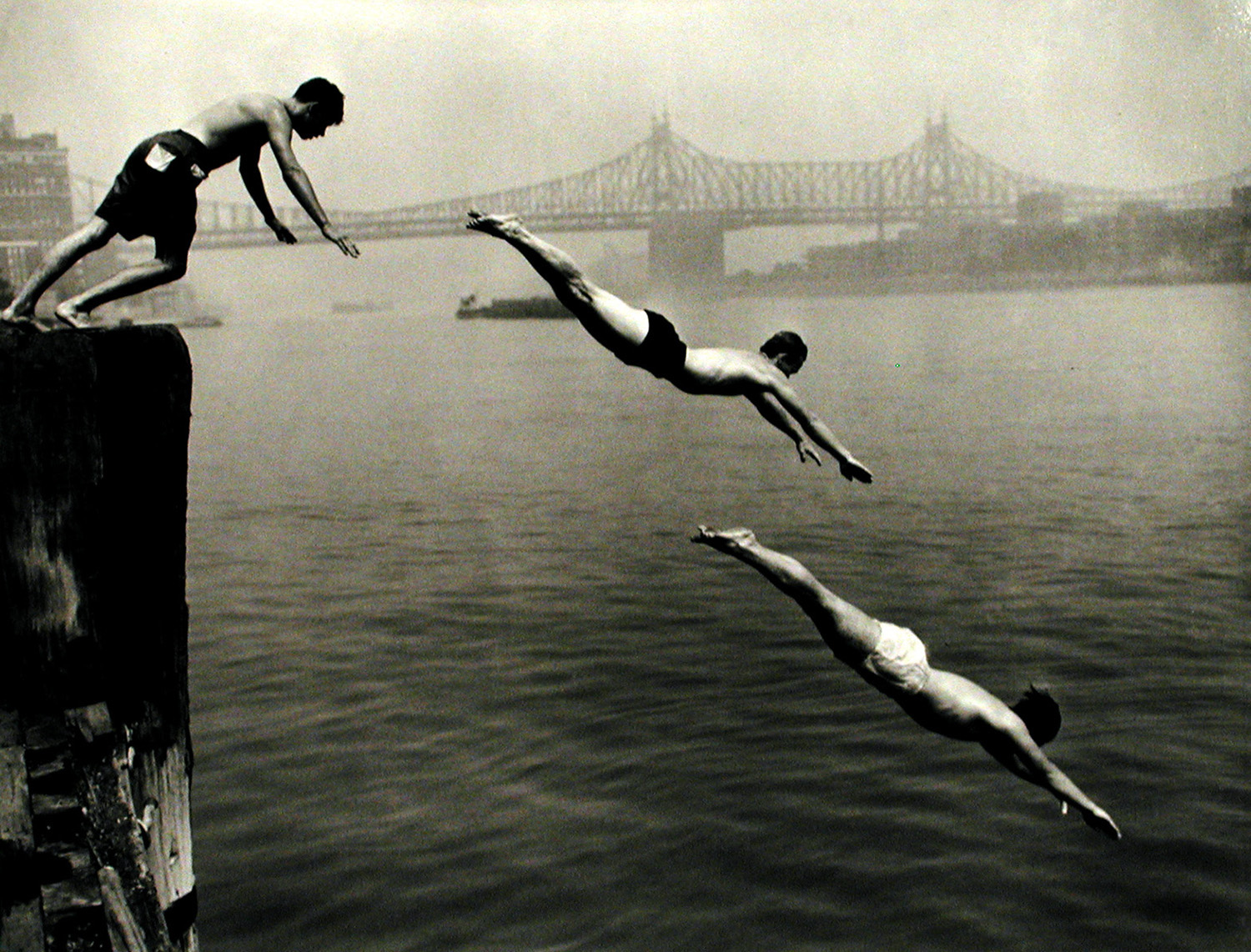

The photography spans from the mid 19thcentury to the present day, and includes works by such blue-chip photographers as Ansel Adams and Diane Arbus. Some of these works address the premise of the show quite directly. Arthur Leipzig’s Divers, East River, captures several youths mid-flight as they leap successively into New York City’s East River. The image, which initially reads like a stop-motion image of a single diver, bears an arresting resemblance to the experimental photography of Eadweard Muybridge.

Arthur Leipzig, Divers, East River, 1948, printed later. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, purchase.

The most literal example of Nature Morte in the show is likely Jersey Crows, an ensemble of photos by Kiki Smith which portray some disorienting close-ups of what appear to be dead birds—actually strikingly realistic bronze sculptures. Other works address the show’s theme much more tangentially. Edward Watson’s Two Shells is an elegant but disorienting image of one shell nestled inside a second shell so as to appear to be a single form. Presented in this unfamiliar way, the organic forms seem more like an abstract sculpture by Barbara Hepworth.

A Brief History of Art in Space and Nature Morte were, of course, conceived as separate shows, but there are some moments where we might find some incidental overlap. Looking at Anders’ Earthrise, one can’t help but interpret it as precisely the opposite of Nature Morte, which is what lent the image such potency. Taken during the height of the Cold War, when the phrase “Mutual Assured Destruction” had entered common political discourse and when schoolchildren were learning to “duck and cover,” the image helped humanity pause and come to grips with the fragility of the planet and the need to preserve it, lest the earth itself become the consummate example of Nature Morte.

East Lansing, Michigan State University, Broad Museum – NATURE MORTE, through August 11, 2019.