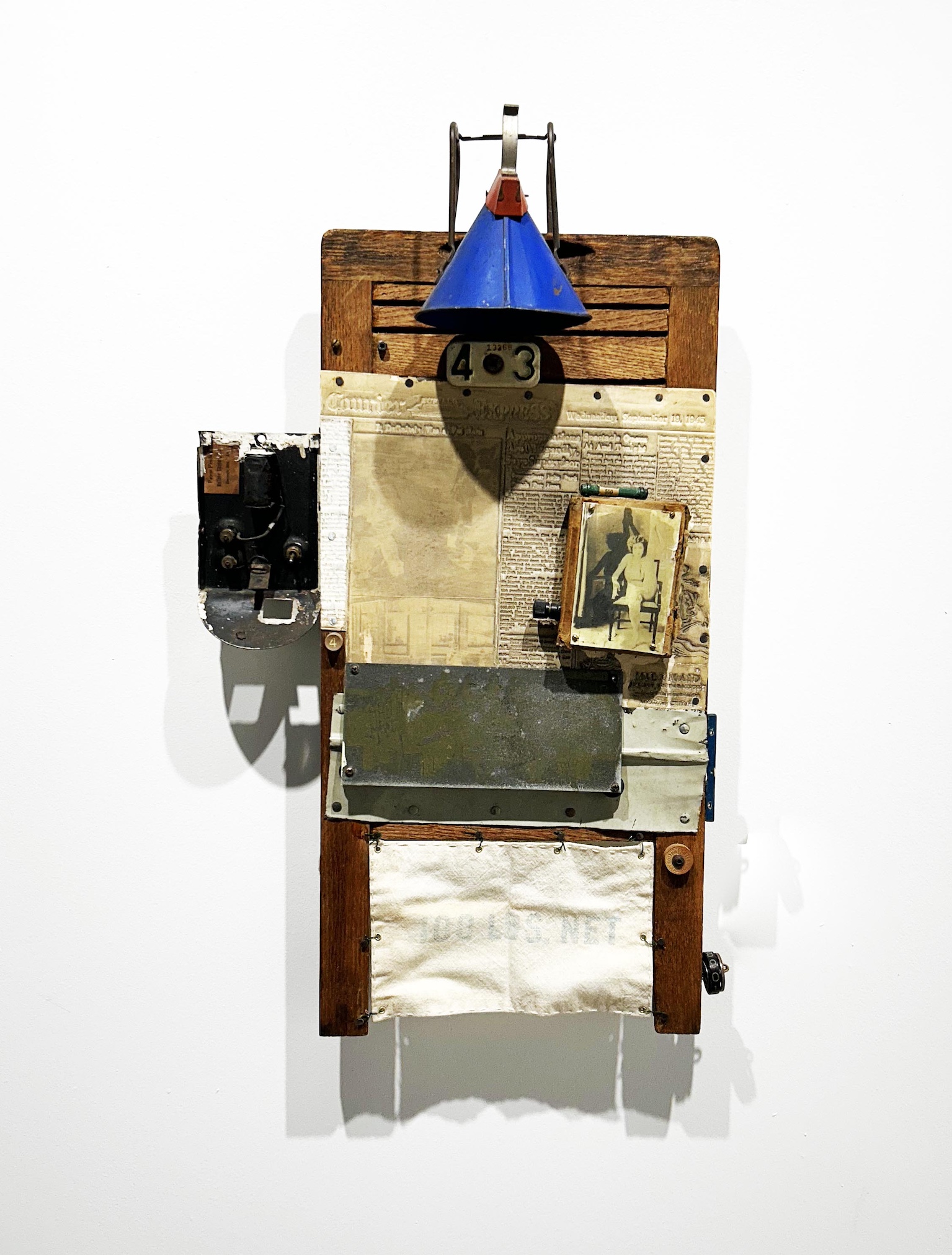

David Barr: Structural Relief, at Collected Detroit through April 13, 2024

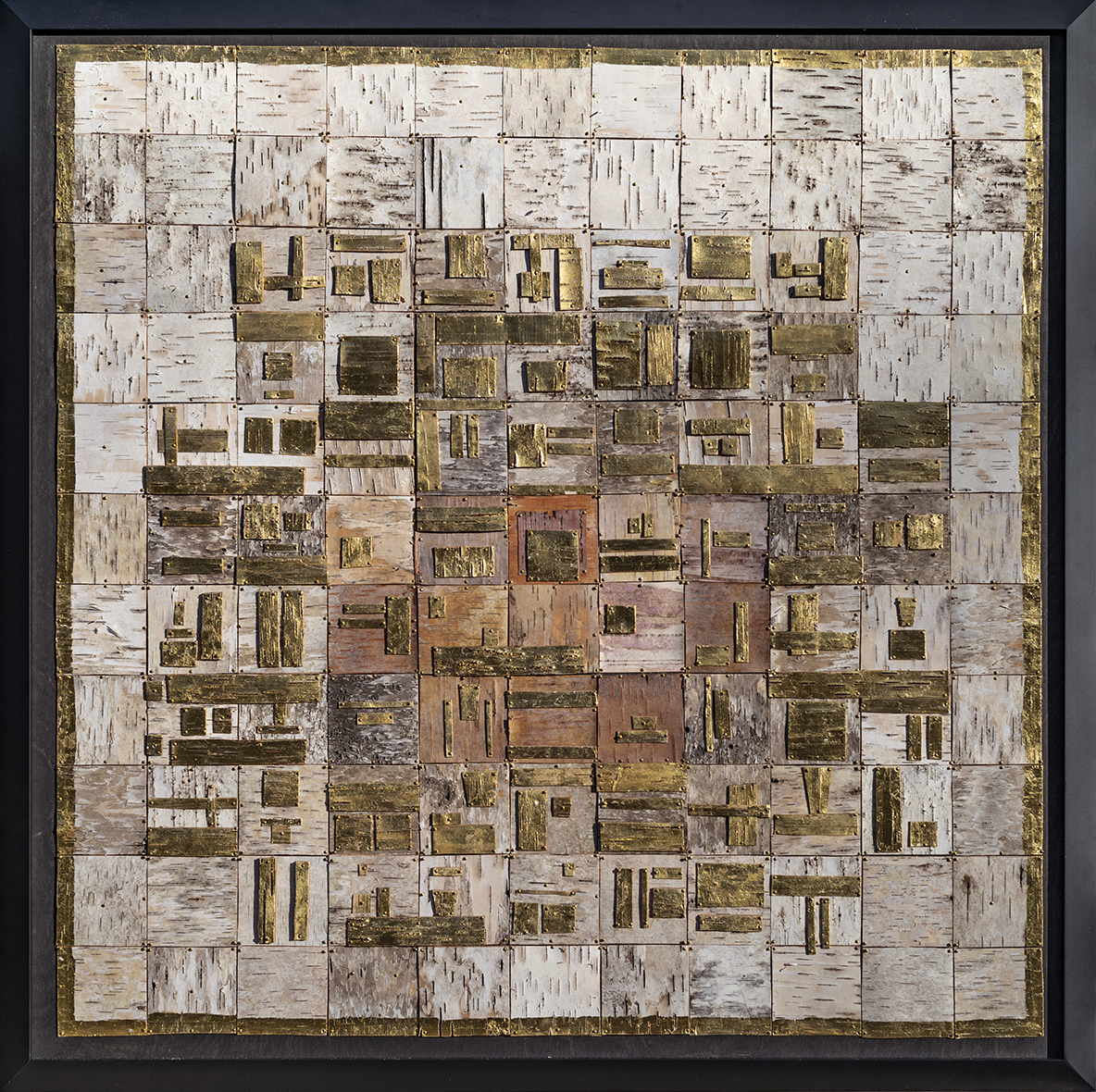

An installation view of David Barr: Structural Relief, which is at Collected Detroit through April 13. Images courtesy of Detroit Art Review.

Novi artist David Barr, who died in 2015, was a creative polymath whose work ranged across media, including giant metal sculptures, wooden-relief wall hangings of great precision, and lithographs documenting a preposterous geometric intervention in the earth’s crust.

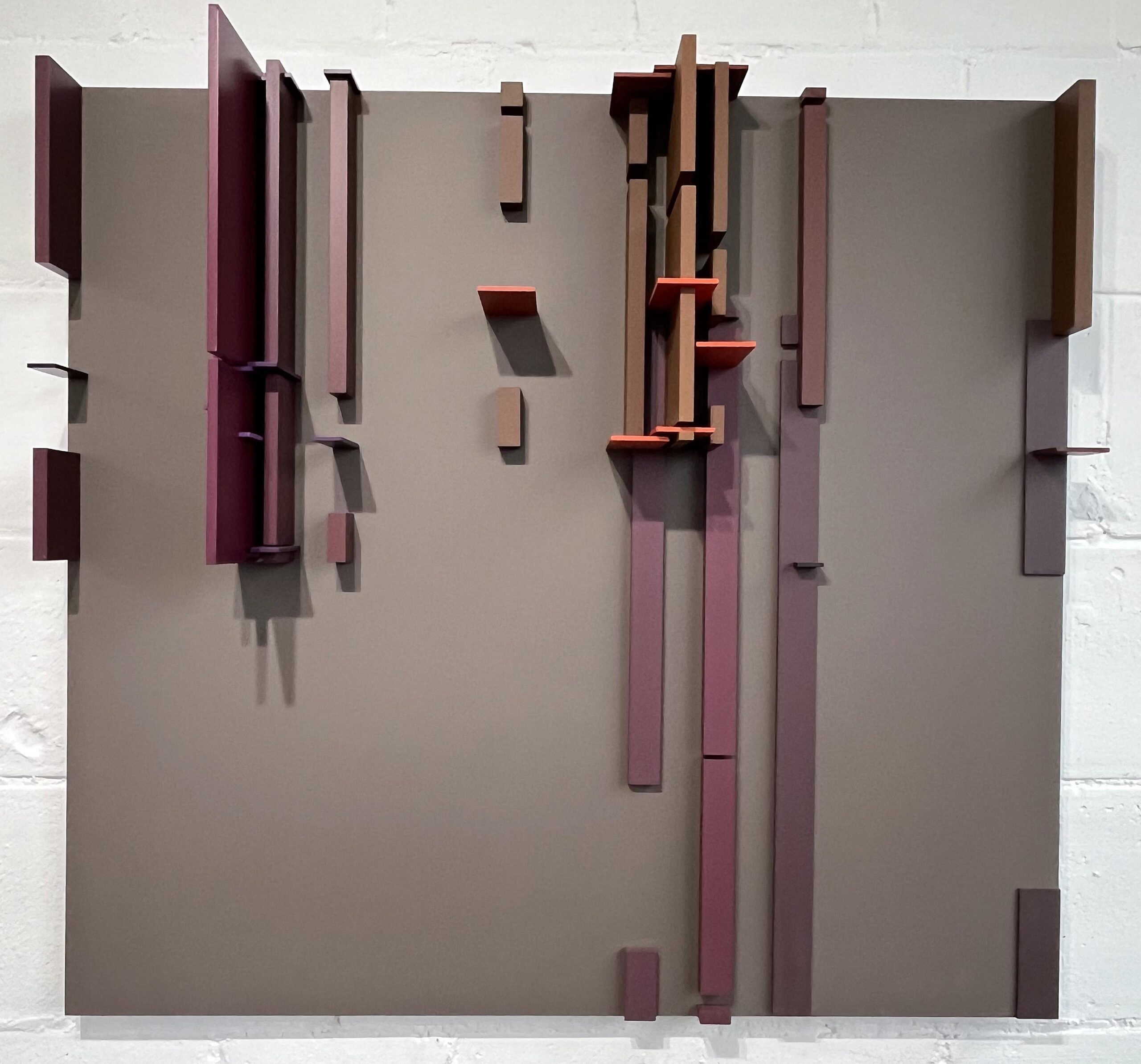

David Barr: Structural Relief at Collected Detroit gallery through April 13 focuses mainly on the artist’s multiple “structurist reliefs,” large, 3-D wooden wall hangings with layered straight lines and curves of varied colors that achieve an almost immediate architectural presence.

The exhibition was curated by Leslie Ann Pilling of the Metropolitan Museum of Design Detroit.

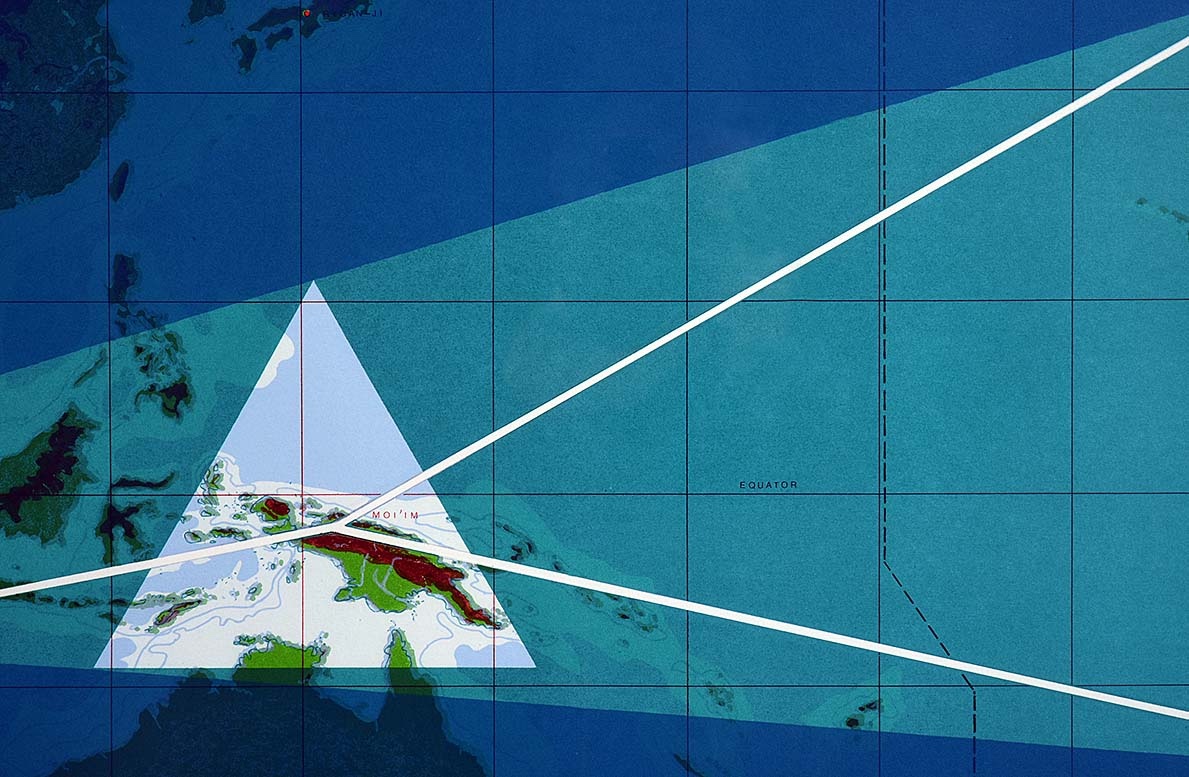

Also on the walls are the four rather elegant lithographs that “document” Barr’s Four Corners Project, which the Archives of American Art spotlit in a 1985 film for the Smithsonian Institution. In the early eighties, Barr enlisted the University of Michigan’s Institute of Mathematical Geography to figure out how to embed an imaginary tetrahedron – a pyramid – in the earth, with its four corners just poking through the soil in South Africa, Easter Island, Indonesia and Greenland. Barr traveled to each site to mark it with a small marble pyramid.

David Barr, Four Corners Project, Lithograph, 1981. Image courtesy of Collected Detroit.

But it’s the structurist reliefs that occupied most of Barr’s attention for several decades, and the geometric works on display here in Collected Detroit’s airy, fourth-floor digs are defined by crisp, sharp-edged lines, whether straight or curved. As noted, at times, these multi-layered compositions seem to leap out of an architect’s sketchbook. Structurist Relief No. 104 leans particularly hard in this direction, with its floating planes and cubes – see the detail below – looking a bit like something that might have emerged from Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus Studio, circa 1928.

David Barr, – Structurist Relief No. 104; Mixed Media 44.5 by 48 inches, 1974.

David Barr, Detail, Structurist Relief No. 104; Mixed Media 44.5 by 48 inches, 1974.

Barr, who grew up in Grosse Pointe, was going to follow in the footsteps of his father, a Chrysler engineer. However, once enrolled at Wayne State, the young man found himself unexpectedly seduced by the fine arts. Barr ended up focusing on sculpture and industrial design, borrowing materials and concepts from the engineering trades that he deployed in installations and reliefs. After graduating in 1965 with a Master’s in Fine Arts, the artist began a lifelong career as a professor teaching at Macomb Community College.

Exactly thirty years later, Barr founded what in many respects might be his greatest contribution to the arts — Benzie County’s remarkable Michigan Legacy Art Park near Crystal Mountain, with 40 sculptural installations along 1.6 miles of forest paths that wind through 30 acres of deep woodlands. Installations include his lumber-industry Sawpath series, as well as other remarkable pieces of great size by Lois Teicher, Sergio DeGiusti, David Greenwood, Leslie Laskey and Joe Zajak, among others.

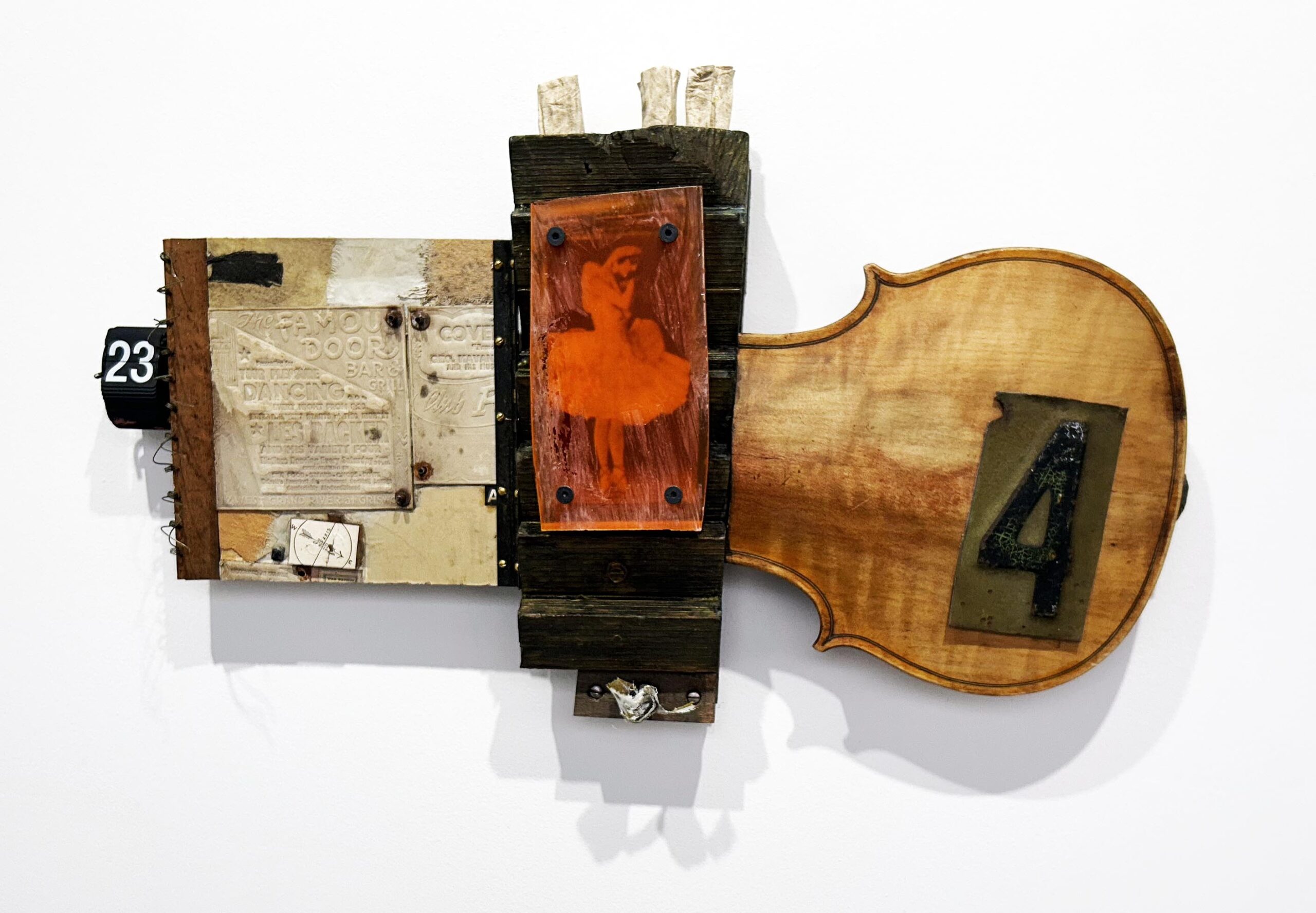

David Barr, Structurist Relief No. 310; Mixed media, 41 by 47.5 inches, 1991.

But Barr never abandoned his trademark reliefs. And over time, the compositions seemed to stretch and assert themselves in new ways. A budding sensuousness crept into what initially had been a mostly rectilinear universe. Starting in the 1980s, curvaceous forms began to compete with narrow verticals in charged juxtaposition, as in the rather breathtaking Structurist Relief No. 310, above.

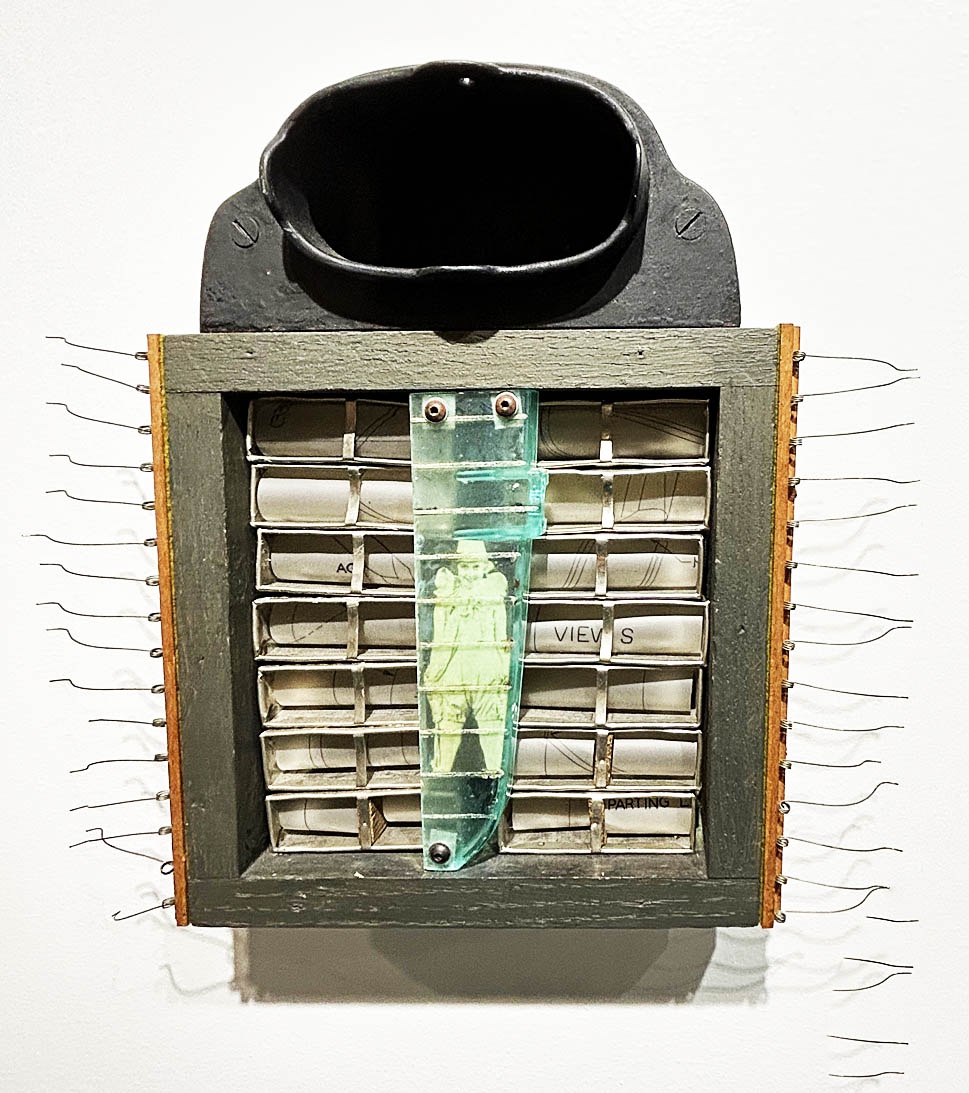

Surfaces began buckling and cracking, spurning the strict geometry of Barr’s early years, as with Structurist Relief No. 271 from 1986. But even here, while the edges may be curved or slightly irregular, each element, as with the pink pieces below, still occupies a single plane. No waves or undulations are to be found.

David Barr, Detail – Structurist Relief No. 271; Mixed media, 50 by 66 inches, 1986.

Curator Pilling says she was immediately mesmerized by the shadows that the elements in the reliefs cast. She adds that the works’ unusual magnetism can be read in the way visitors progress through the gallery. “People spend time with each relief,” she said. “A lot of times people going through exhibitions are, like: Walk, walk, stop, walk, walk. But this is more: Walk, walk, STOP. They really take them in.”

If you haven’t been to Collected Detroit since the pandemic, be aware that the gallery has moved from its first-floor location on Fourth Street just around the corner. It’s now on Henry Street, on the top floor of an adjacent building.

Also well worth a look if you visit the gallery are freestanding works here and there by Harry Bertoia, Joseph E. Senungetuk, Detroit’s legendary Charles McGee and, most astonishing, the Hollywood actor Anthony Quinn. The sinuous “Nude” that this Renaissance man sculpted out of marble sits on a ledge right by a window, one ankle resting delicately on the other, cool as a cucumber.