The work of Nanette Carter is joined by Al Loving, Sam Gilliam, and Gregory Coates at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art

A Survey, Thirty Years of work by Nanette Carter, Install Image courtesy of DAR

The new exhibition at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art centers on the artwork of Nanette Carter and three of her contemporaries. All the work is based on various ways to approach the depth and variety of abstraction. The exhibition surveys thirty years of work going back to 1983 when N’Namdi first exhibited the work of Nanette Carter. The video below gives the reader an in-depth explanation of her artwork where she talks about using oil paint on mylar and then cutting up and arranging forms, shapes, color, and line to express a unique composition. Here, she takes the viewer through her process that begins with a small drawing.

Nanette Carter, Bouquet for Loving #17, Oils on Mylar, 57 x 50″ 2011

Carter has developed a painting style that consists of abstract designs and effects superimposed on top of each other in ways that emphasize chance but often reflect a theme as in the artwork Bouquet For Loving #17. Carter does not precisely follow a particular tradition, and that’s evident in each of her works, which are stand-alone concepts to which she brings materials such as fabric into her oil paint on mylar world.

Nanette Carter, Aqueous #49, Oil Collage on Mylar, 46 x 53″ 2008

An example is a work Aqueous #49 where Carter elegantly composes a circular composition using her mylar collage on an expansive surface of textures based on an organic color palette. The random placement of patterned designs within the paintings, along with their slightly free-form outlines, establishes Carter’s desire to work both inside and outside the conventions of her genre.

Nanette Carter earned her B.A. at Oberlin College where she majored in Art and Art History.

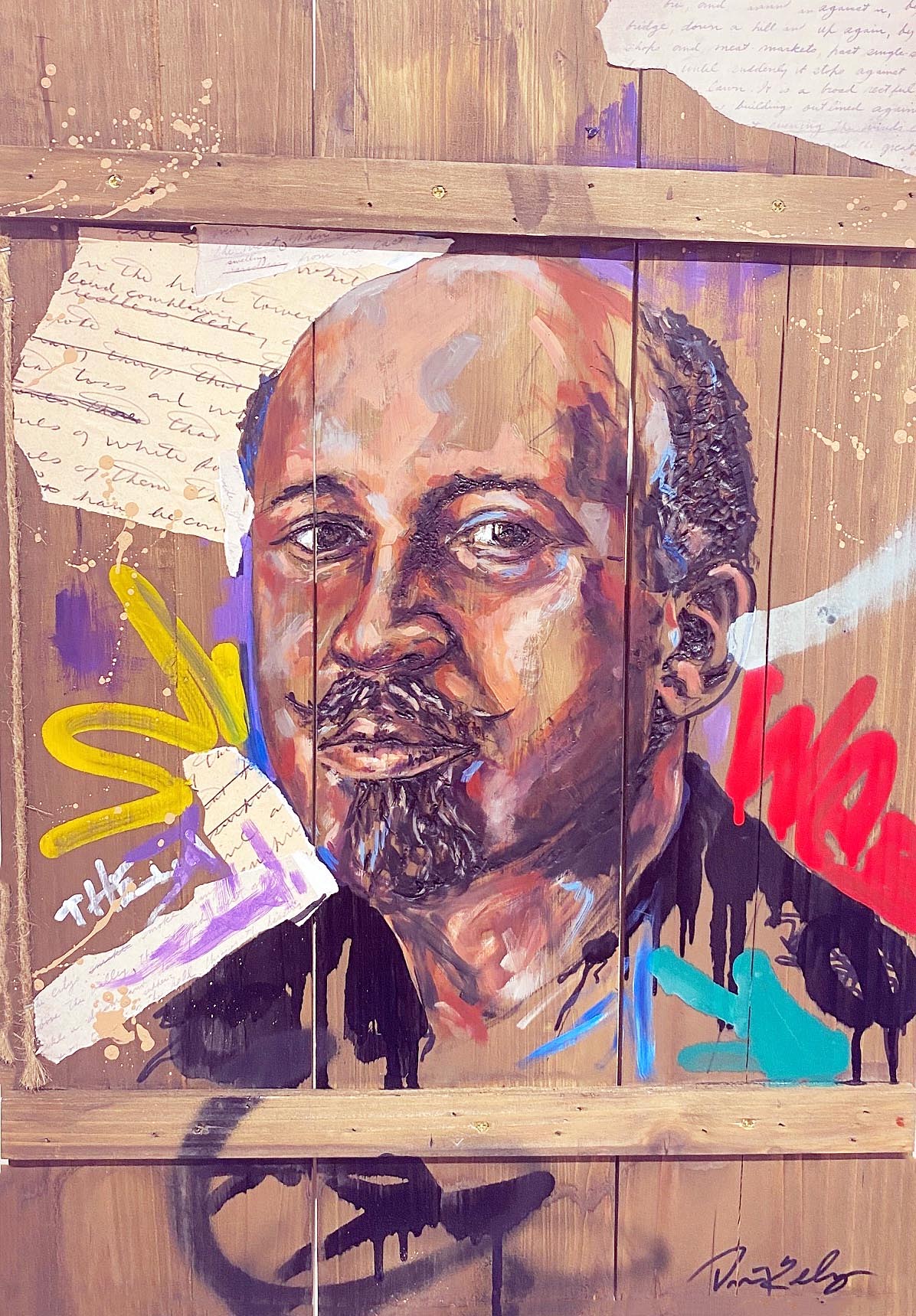

Al Loving, Red Hook #1, Mixed Media on Board, 38 x 28″

Born in Detroit in 1935, Al Loving studied painting at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor. After graduation, he relocated to New York where he found himself among a social group that included artists Robert Duran and Sam Gillian. In 1969, Loving famously became the first Black artist to have a one-person show at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In the work Red Hook, Loving showcases his traditional spiral shapes creating a more organic abstraction. A kind of shaped canvas relief on the wall, the mixed media piece draws primary colors together in a collage-type construction. His work became known for using geometric shapes and shaped canvases where he was drawn to corrugated cardboard and rag paper.

Sam Gilliam, In The Fog, Relief, hand-sewn, acrylic on hand-made paper, 36 x 48″, 2010

The color field painter is recognized for representing the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2017. Gilliam was born in 1933 in Tupelo, Mississippi, and grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. The Black painter and lyrical abstractionist artist are associated with the Washington Color School, a group of Washington, D.C.-area artists who developed abstract art from color field painting in the 1950s and 1960s.

His works have also been described as belonging to abstract expressionism and often a more lyrical abstraction. He works on stretched, draped, and wrapped canvas and adds sculptural 3D elements. He is recognized as the first artist to introduce the idea of a draped, painted canvas hanging without stretcher bars around 1965, and this was a major contribution to the Color Field School.

Gilliam has worked with polypropylene, computer-generated imaging, metallic and iridescent acrylics, handmade paper, aluminum, steel, plywood, and plastic in his more recent work. Sam Gilliam earned a B.A. and his M.A. at the University of Louisville.

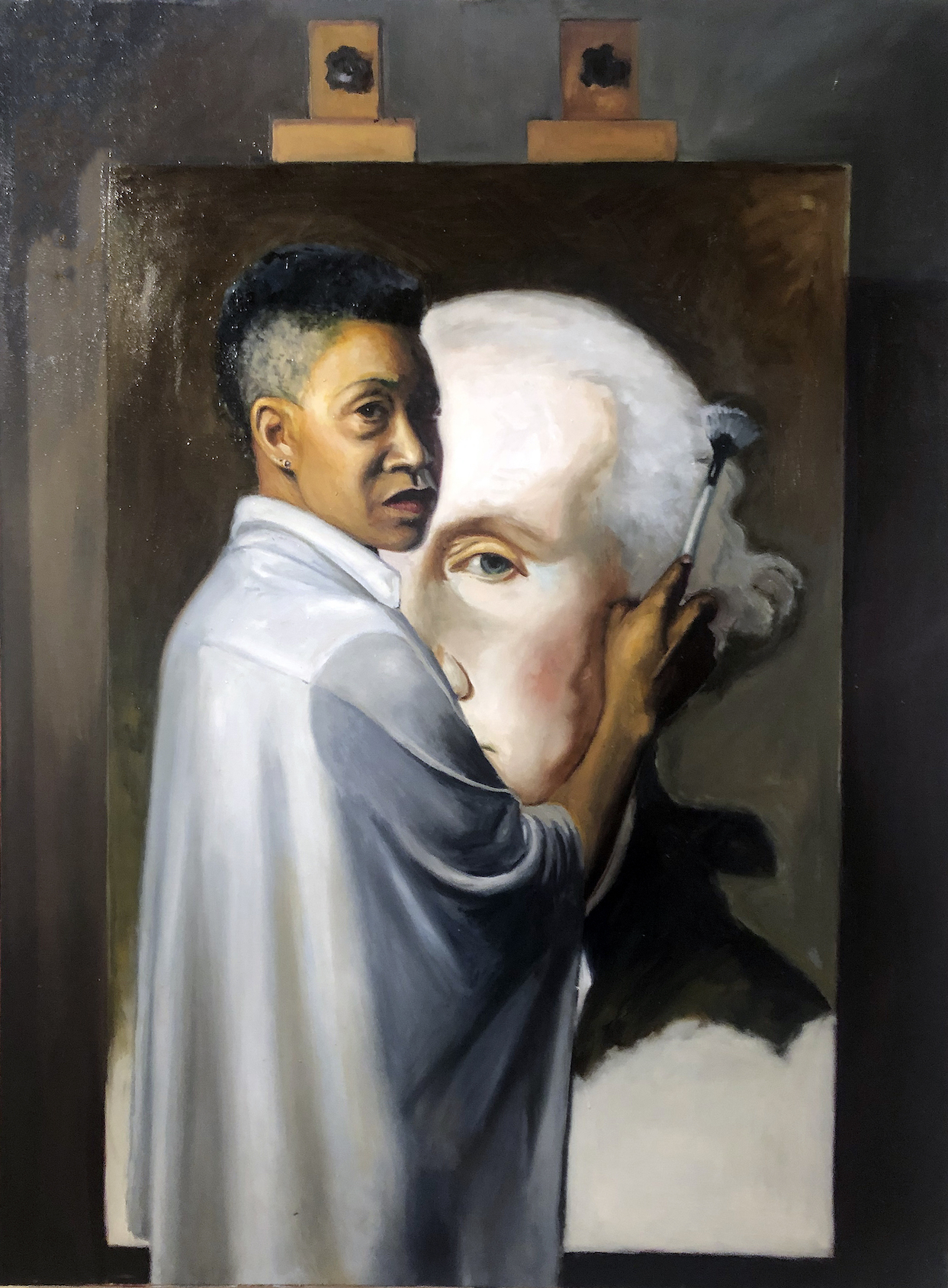

Gregory Coates, I Made It, Mixed Media on Wood, 48 x 45″

Gregory Coates was born in Washington D.C. in 1961 and grew up in the northeast part of the district. He is a Black artist known for working in the realm of social abstraction. In this exhibition, the work I Made It is a composition of concentric circles of various sizes on an orange-red background.

Gregory Coates attended the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., from 1980-1982 and later the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1990.

George N’Namdi founded G. R. N’Namdi Galleries in 1982 in Detroit, Michigan. It is one of the oldest commercial galleries in the United States and features works of contemporary abstract artists. The gallery has established its reputation as the leader in educating and inspiring new and seasoned collectors. They have worked hard at building art collections around Metro Detroit and beyond. Works from the gallery are featured in some of the most prominent public and private collections worldwide.

Nanette Carter & Contemporaries @ N’Namdi is on display through December 31, 2021