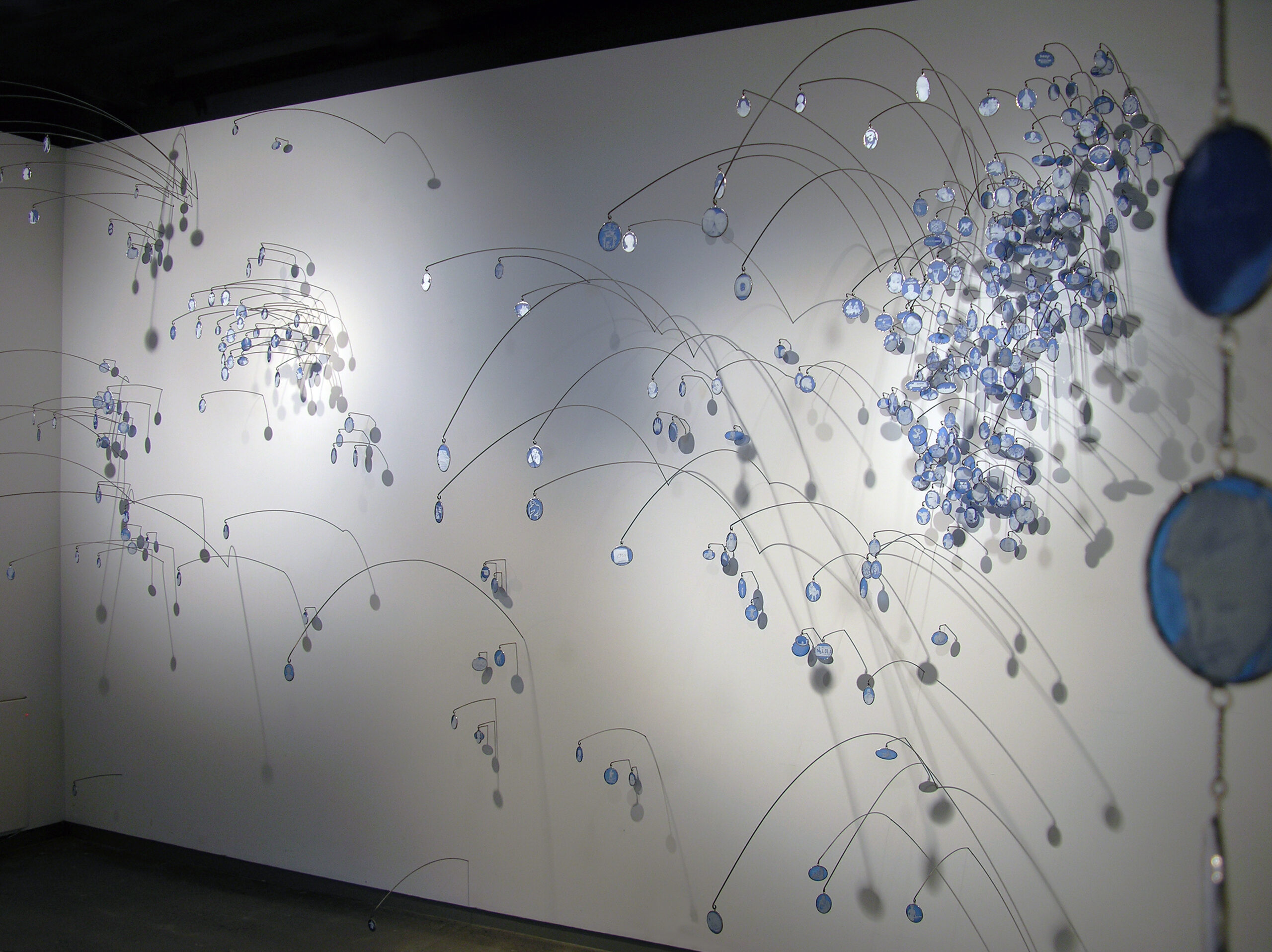

Breaking the Mold, installation, and all images are courtesy of the Flint Institute of Arts.

Whenever I visit the Flint Institute of Arts, I always leave feeling that the FIA is a seriously under-hyped museum, not just because of the strength of its collection but also because its galleries are just downright cool spaces, each varied and perfectly suited for the time period and style of the artwork they contain. A major expansion in 2018 added to these galleries a chic and suitably contemporary space to showcase the museum’s collection of modern and contemporary glass. Until April 2, many of these glass works join forces in the Harris-Burger Gallery (also a relatively new addition) with works pulled from storage to offer a visual survey, European Cast Glass, offering viewers an intimate single-room micro-exhibit that hints at the diversity and the surprisingly subversive beauty of the medium.

It’s a show entirely of European cast glass, offering a truncated survey of the medium while suggesting its enduring relevance. The method of using a mold to cast glass dates back to the 15th century BC, long predating the development of blown glass, a first-century innovation. The 20th century brought about a Renaissance of glassmaking in Europe, fueled by artists who began their careers in manufacturing but broke away from commercial glassmaking and focused instead on glassmaking as fine art.

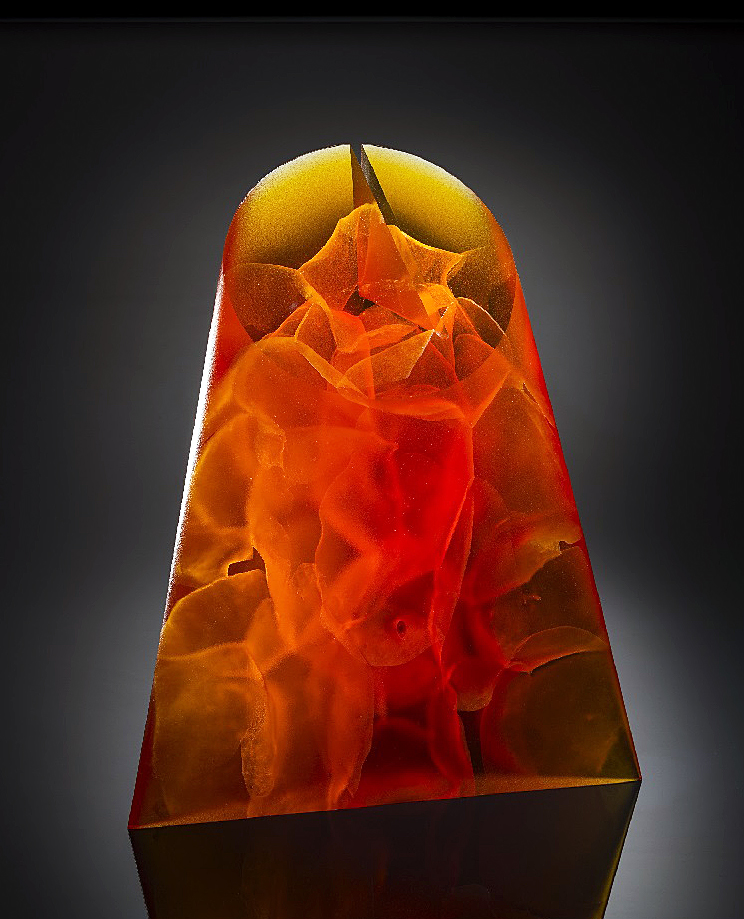

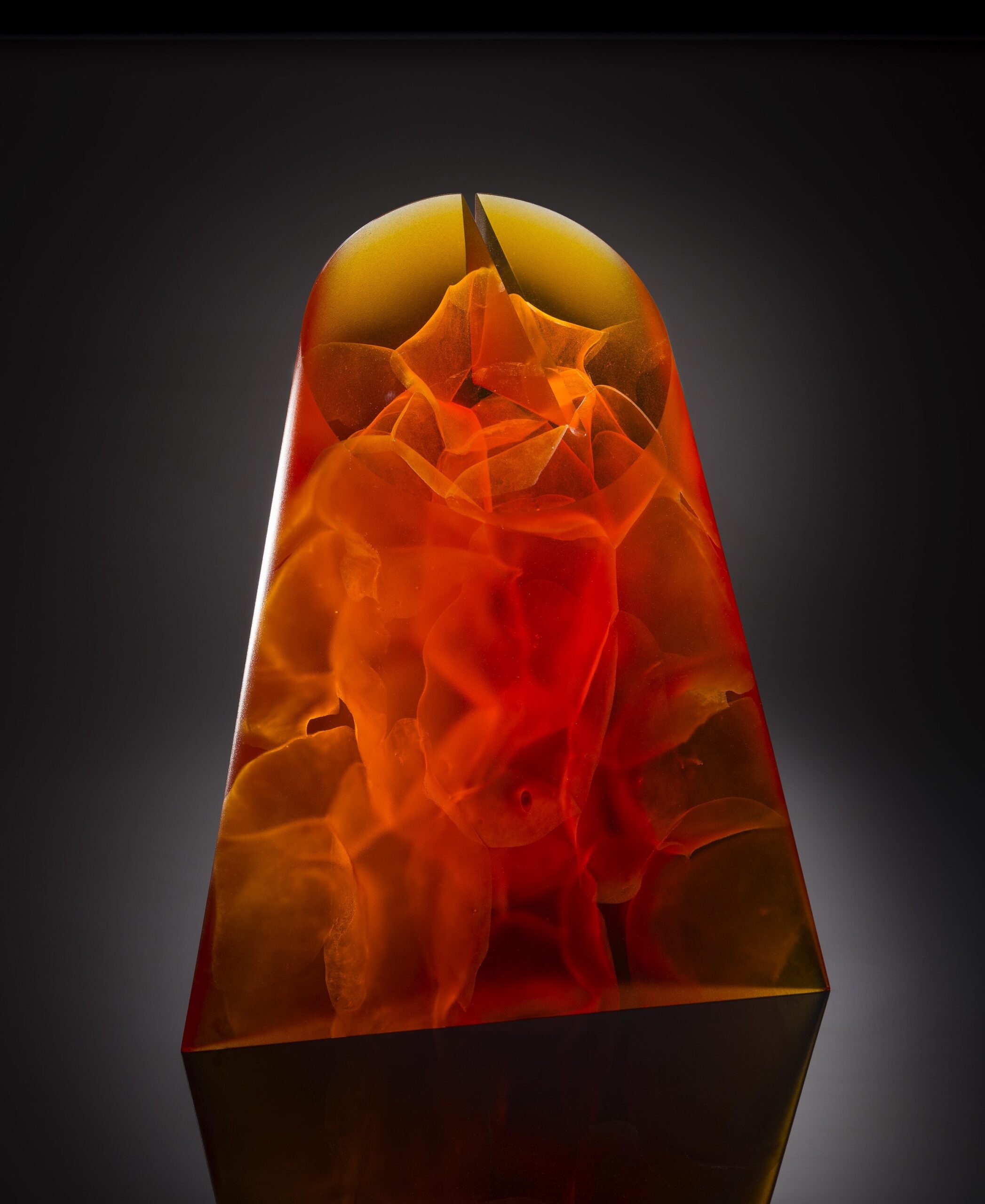

Petr Hora, Czech, born 1949, Hadros, 2006. Cast and acid-polished glass 18 3/4 × 15 1/2 × 4 3/4 in. (47.6 × 39.4 × 12.1 cm). Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation. L2017.59. Photo Credit: Douglas Schaible Photography.

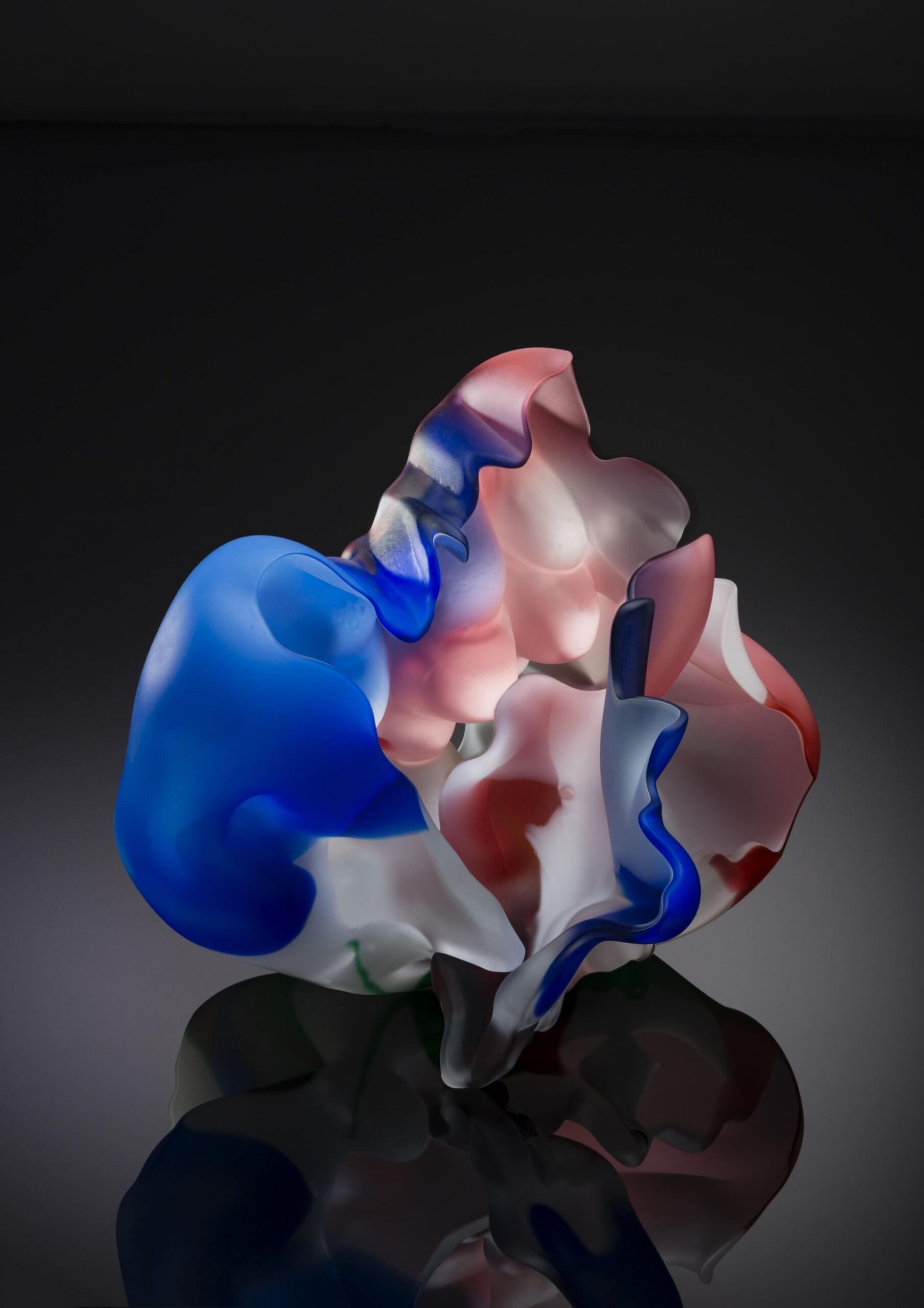

Vladimira Klumpar Czech, born 1954. After Rain, 2007, Cast glass. 33 3/4 × 23 1/2 × 8 3/4 in. (85.7 × 59.7 × 22.2 cm). Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation. L2017.67. Photo Credit: Douglas Schaible Photography.

Most of these works are abstract or non-representational, but not all. North Sea Waves by Slovakian artist Zora Palová is a vertically oriented column of gently undulating waves of glass. Unlike many of the works in the exhibit, which have clean, crisp lines, North Sea Waves has a very textural, rough surface, revealing the hand of the artist. In her choice of dark violet and white, Palová wanted to mimic the color of crashing waves of the North Sea, and in this work, she presents us with a seascape playfully flipped on its axis (having lived for a while in St. Andrews, Scotland, I can vouch with Palová that the North Sea can certainly get dark, and moody).

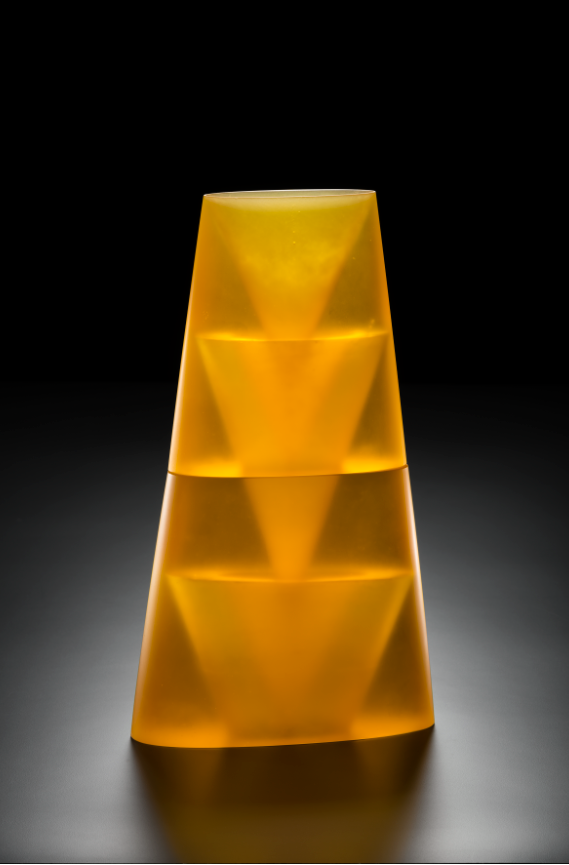

Many of these artists were simply exploring the capabilities of color, shape, light, and form, and their works seem largely the result of play and experimentation. The organic appearance of Vladimira Klumpar’s After Rain is delightful, vaguely organic in form, reminiscent of some kind of otherworldly plant gently bending from the weight of droplets of liquid glass. And the vertically ascending triangles of Vladimir Bachorik’s Escalation, to me anyway, read almost as an inverted stack of highly abstract nesting dolls. Depending on the thickness or thinness of the glass, the color of these abstract works can alternate between rich and opaque or thin and translucent.

But some of the works in this exhibit are charged with surprising social and political relevance. Stanislav Libenský and his wife Jaroslava Brychtová are both represented in this exhibit with several works. Heavily influenced by Cubism and Constructivism, their work stood as a subtle foil to the government-sanctioned Soviet-realist style so prevalent in Eastern Europe, something they had in common with other Czech artists. Together they innovated methods for casting monumental cast glass, and became renowned artists and teachers with an international following. Many of the artists in this show followed in their footsteps, and Sarah Kohn– the exhibition’s curator– likens this show to a sort of visual “family tree,” allowing us to see how these artists influenced each other.

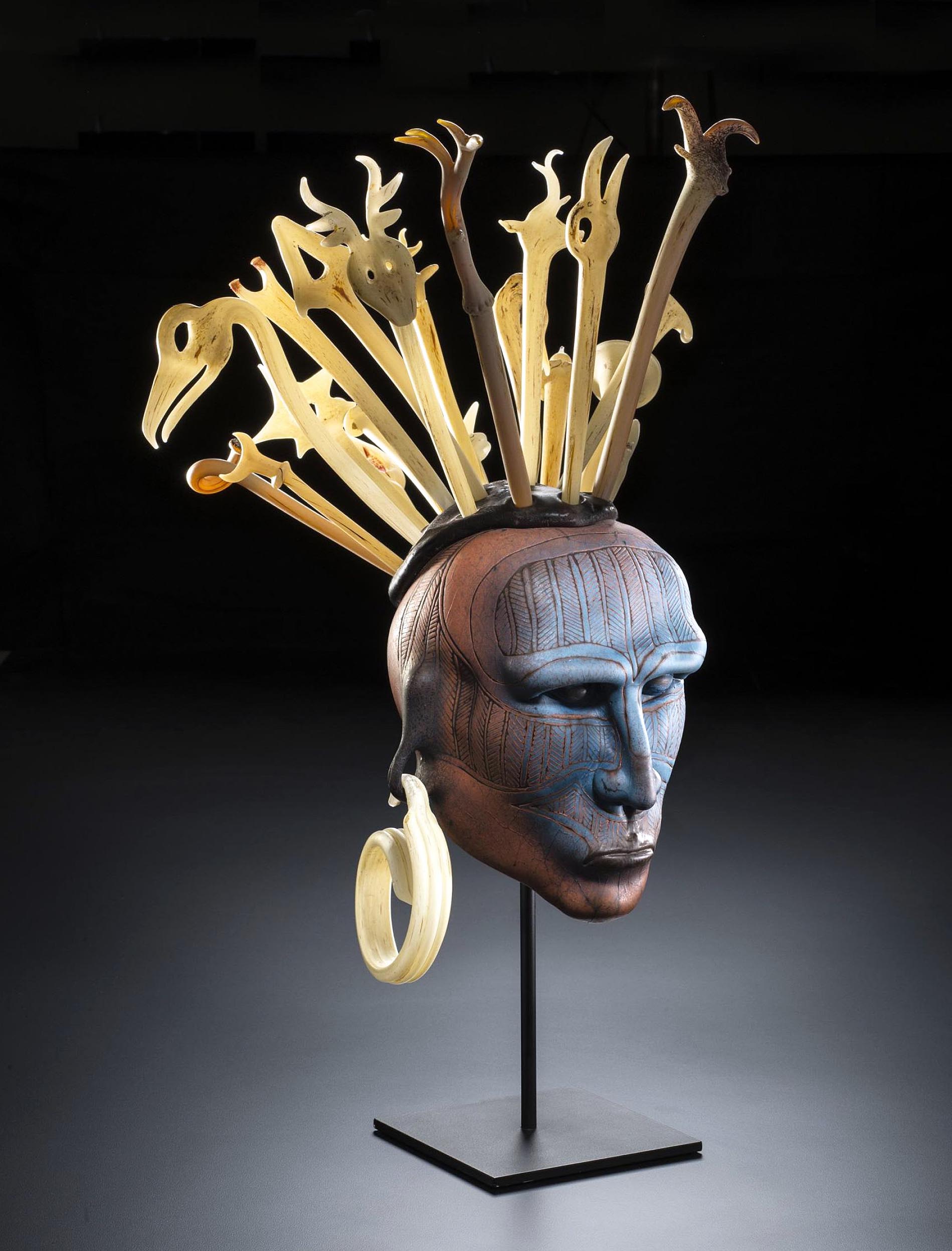

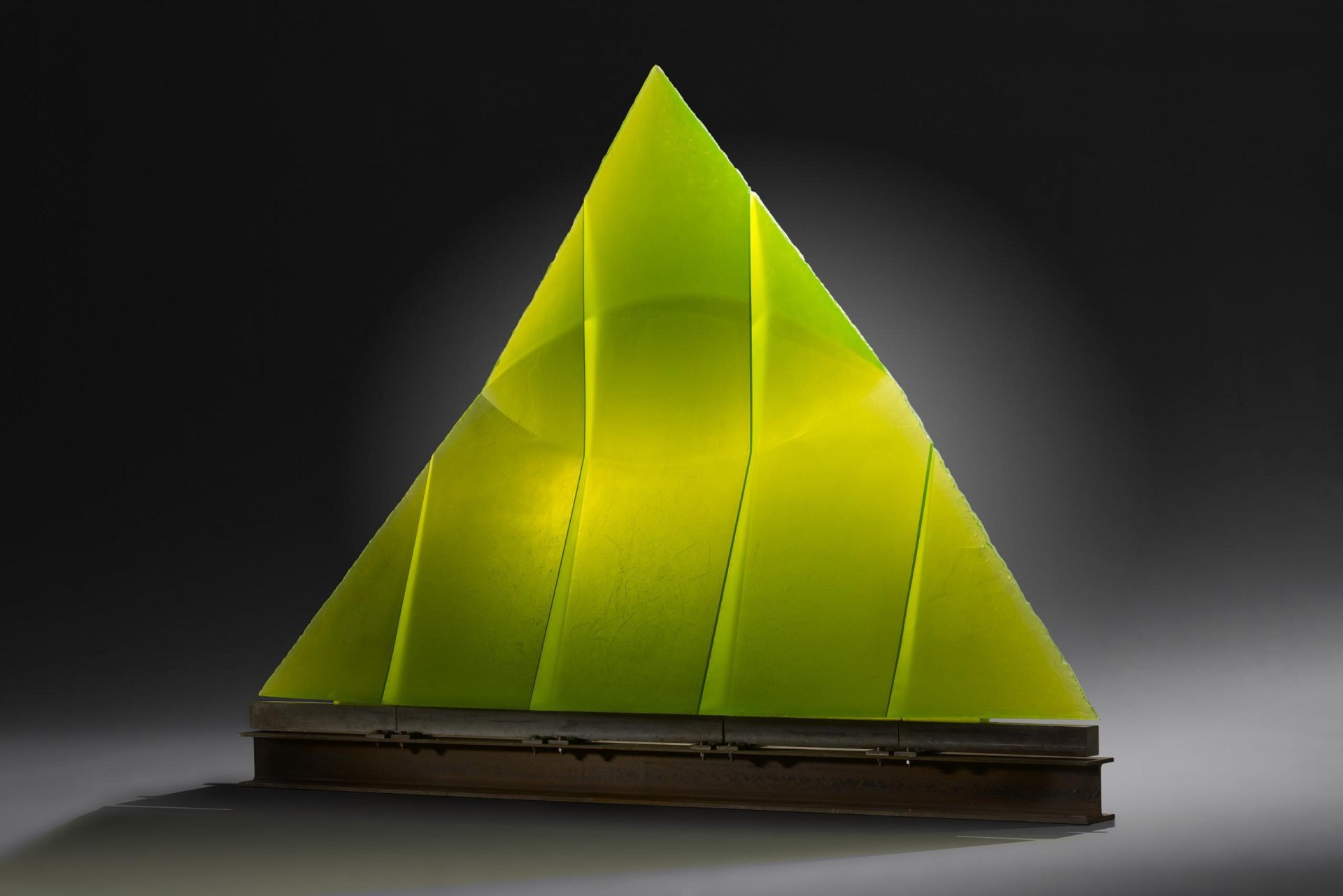

Vladimir Bachorik Czech, born 1963, Escallation, 2005 Cast glass. 23 1/2 × 13 1/2 × 4 in. (59.7 × 34.3 × 10.2 cm). Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation. L2017.13. Photo Credit: Douglas Schaible Photography.

Stanislav Libenský Czech, 1921 – 2002 Horizon, 1992-2005 Cast glass, 33 × 43 × 11 1/2 in., 500 lb. (83.8 × 109.2 × 29.2 cm, 226.8 kg). Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation. L2017.74. Photo Credit: Douglas Schaible Photography.

Stanislav Libenský’s 3V Column, the exhibition’s literal centerpiece, was a direct response to Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, which Libenský witnessed firsthand from his studio window. The half-million protesters who in 1989 gathered in Wencelas Square and collectively brought an end to Communist one-party rule flashed their fingers in a Churchillian V Shape: a shape directly referenced by the horizontally oriented V-shaped cuts incised in three different places in the column. The column was previously displayed in the FIA’s glass gallery on a podium against a wall, but here it’s in the center of the gallery space, allowing viewers to appreciate it in 360 degrees, and view up close the thousands of minuscule air bubbles arrested within its form.

Breaking the Mold allows the FIA to flaunt highlights from its robust collection of glass art, including works previously in storage. It also re-presents the way some of these works are displayed, yielding a different viewer experience. Even if the historical context or subject of a work of glass art is not readily apparent, glass still possesses an undeniable beauty that prevents it from being prohibitively esoteric; it’s art that anyone can enjoy. This is a small exhibit, so come for what it is, and while you’re there, explore the rest of the much underhyped spaces the FIA has to offer.

Breaking the Mold, installation image courtesy of the Flint Institute of Arts.