Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center presents Stan Natchez, Brenda Kobs Russell, and Maria Balogna

Stan Natchez, BBAC, Install 3.2023

The BBAC opened its three galleries with new visual art exhibitions on March 10, 2023, presenting work by a Native American painter, Stan Natchez, a printmaker, Brenda Kobs Russell, and drawings by Maria Balogna.

Stan Natchez was born and raised in Los Angeles. Still, the indigenous artist now lives in New Mexico and brings his exhibit, Indian Without Reservation, to the BBAC with support from the National Endowment for the Arts and Arts Midwest. By taking the philosophies and techniques of both modern life and the traditional Native American heritage, Natchez achieves a complex harmony in his work by using a distinctive Neo-Pop style. He says in his statement, “I paint the life I live, and so every painting, in some way, is a self-portrait. My art is about the way I respond. And that is my experience…my experience is my art…and art is my life.”

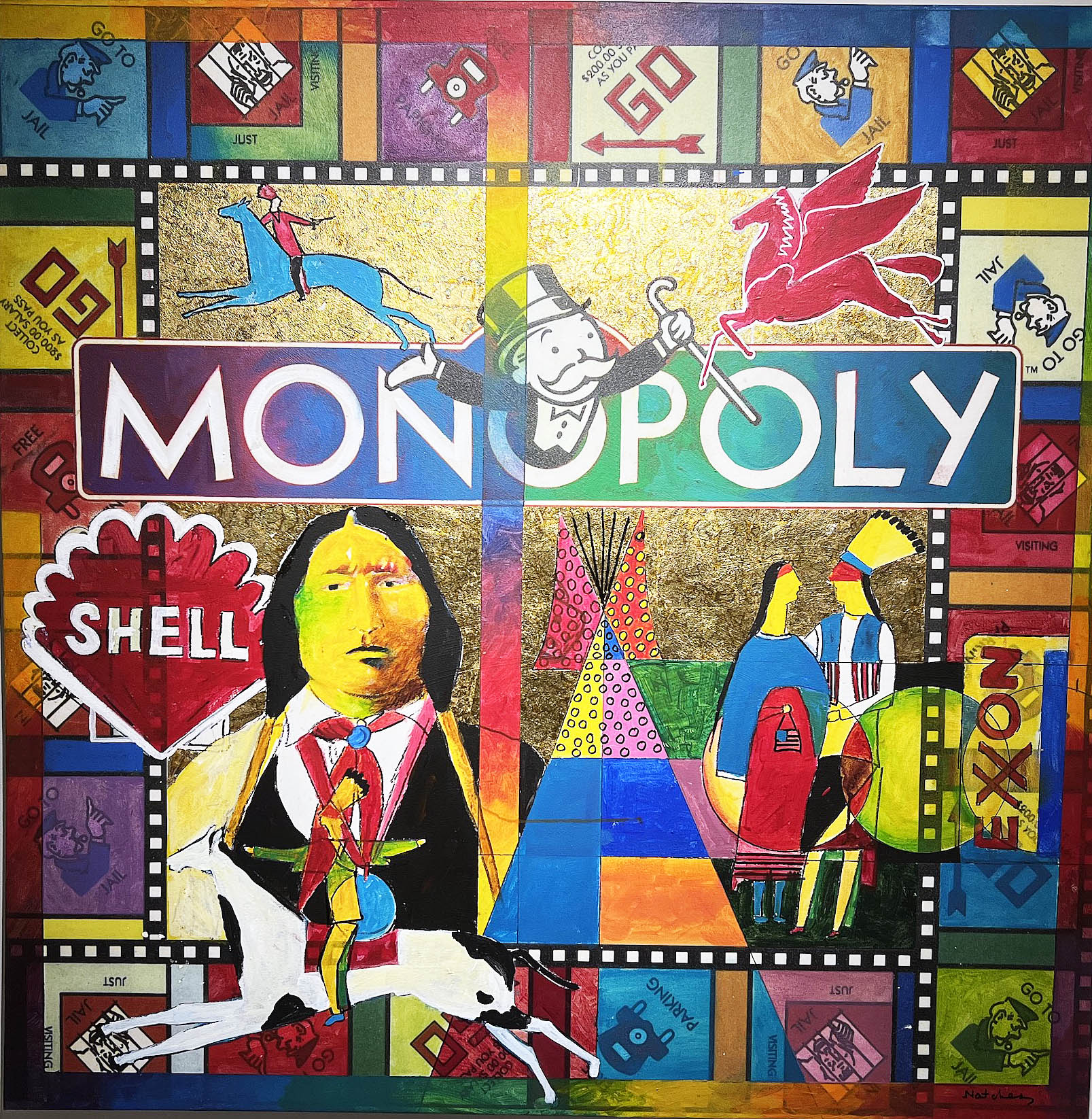

Stan Natchez, Monopoly, 58 x 58″ Mixed Media

Natchez talks about his influences, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Roy Lichtenstein, combined with artifacts from the Native American culture. They would be found in Monopoly, where he uses the popular board game as a compositional structure to combine the various corporate logos with Native figures and designs. (I know this writer has worked hard at eliminating the word Indian from my vocabulary to represent Native Americans, yet I find it ironic to see this in the title of this exhibition.)

Stan Natchez employs art appropriation in most of his work throughout the exhibition, where he uses pre-existing objects or images as an artistic strategy, intentionally borrowing, copying, and image transfer is a practice that is traced back to Cubism, Dada, and, more recently, Pop Art.

Stan Natchez, Medicine Crow Living in Two Worlds, 48 x 36″ Mixed Media

Medicine Crow comes from a warrior of the Crow tribe. He was a “reservation chief,” concerned with helping the Crow tribe “learn to live in the ways of the white man” as soon and as efficiently as possible. The subject for this painting is taken from an original black-and-white photograph. The crow symbolism represents messages from dreams or the sub-conscience, and the object he holds is a group of feathers attached to a wooden handle and is used in a variety of ceremonies. Natchez brings the three primary colors across the face to draw attention to the reservation chief.

Stan Natchez, Traveling Through Time, 48 x 66″, Mixed Media

Natchez travels across time, mixing the images of Picasso, Matisse, Marilyn Monroe, Piet Mondrian, and a section of the painting Guernica juxtaposed with several Crow tribal leaders. He is mixing famous western images with Native American icons across time, creating a grid that compares and contrasts. By doing this, he places his people on par with world-recognizable images.

Stan Natchez, Guernica to Wounded Knee, 48 x 66″ Mixed Media

Part of this painting includes features of Guernica, the large 1937 oil painting by artist Pablo Picasso. Natchez spans time with imagery from events at Wounded Knee. It is one of his best-known works, regarded by many as the most moving and powerful anti-war painting in history. The painting here was made earlier in 2012 and then was sold and duplicated at a later date.

Stan Natchez earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Southern Colorado and his M.F.A. at Arizona State University. In addition to being a nationally known artist, Natchez has distinguished himself as a teacher, dancer, editorial advisor, and legal advocate for the Native American community.

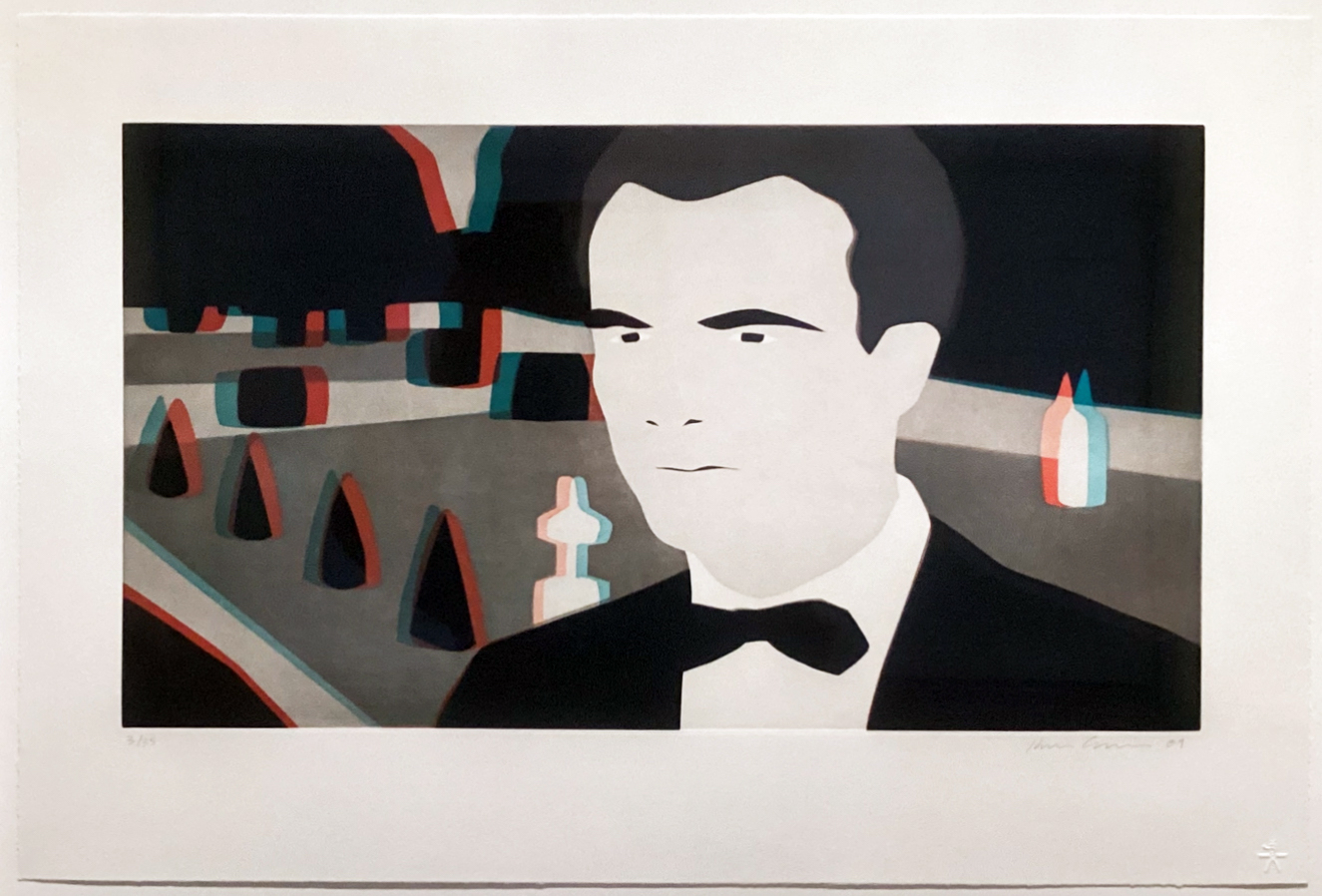

Brenda Kobs Russell: Familiar Rhythms

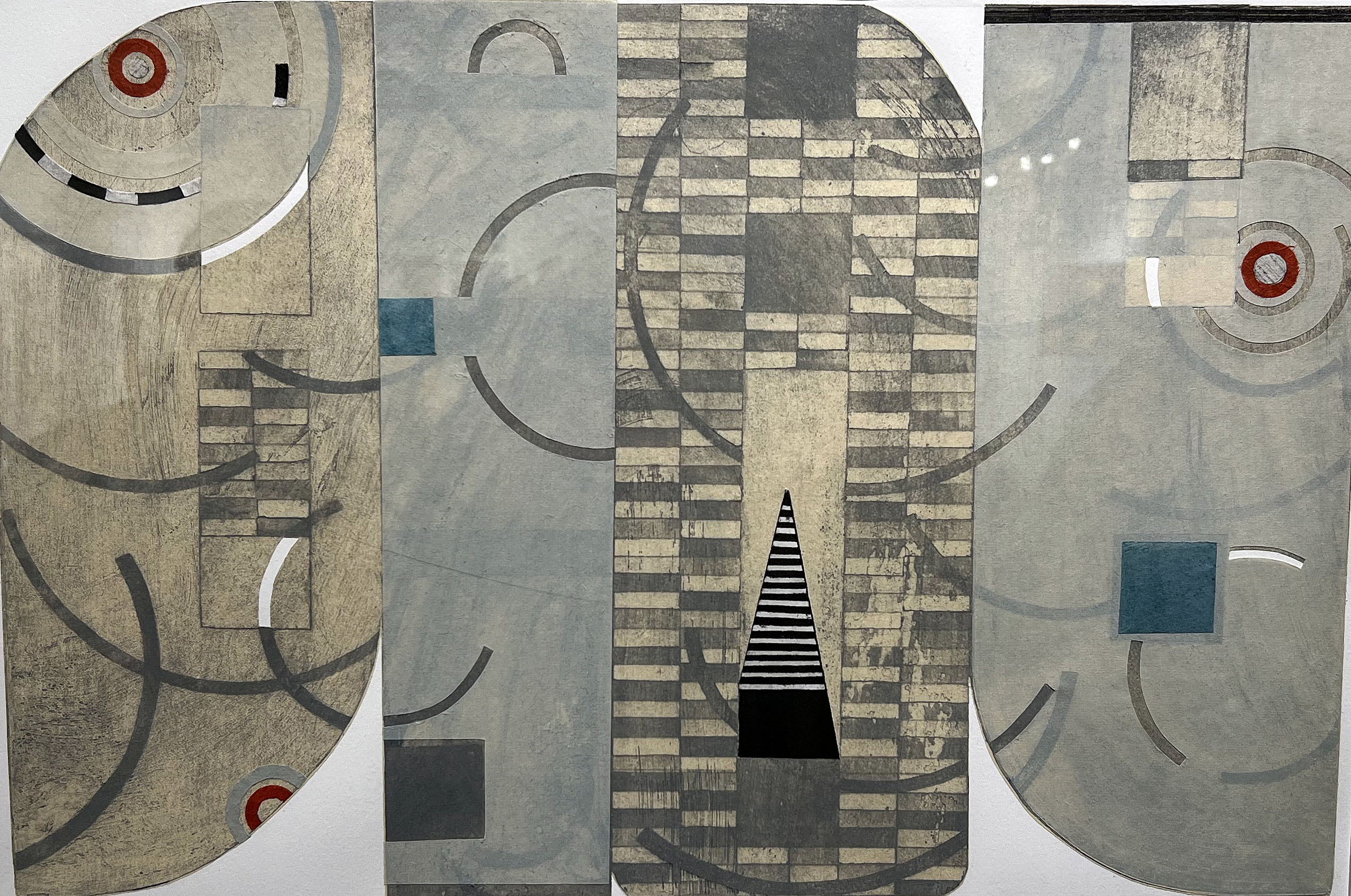

Brenda Kobs Russell, Sequence, Etching Collage

Brenda Kobs Russell is a locally based artist whose work reflects an ongoing investigation connecting her inner life to natural phenomena. Given her time in school, you could look to the abstract influences of Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger, or Paul Klee. During the 1920s, geometric abstraction manifested itself as the underlying principle of the Art Deco style, which propagated the broad use of geometric forms to influence abstraction. For example, Sequence is an etching with touches of white gouache, making it a monoprint that has been popular among printmakers recently.

She says, “As a whole, my work serves as a record, mapping an interior investigation of my surroundings and a practice of abstracting the familiar. I am interested in the congruities between organic cycles of transformation and artistic process, particularly how an image evolves through the erosion of an etching plate and is further translated by ink into paper.”

Russell is an art educator, having taught students across a wide range of ages and abilities in private schools, art centers, and as a lecturer on the faculties of Oakland University and Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design, University of Michigan. She earned her B.F.A. at Michigan State University (1983) and her M.F.A. at Cranbrook Academy of Art (1985).

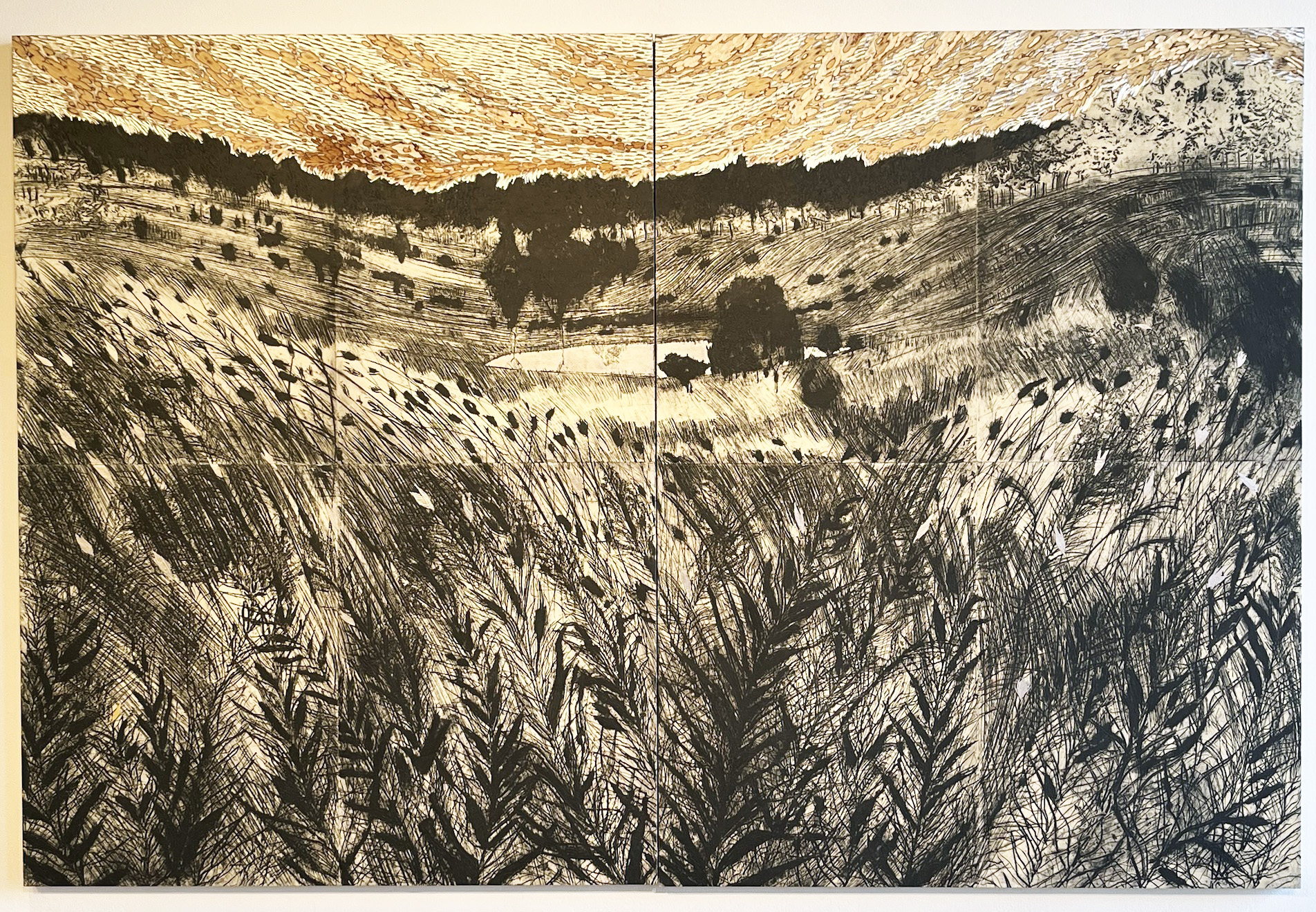

Maria Balogna: by His stripes

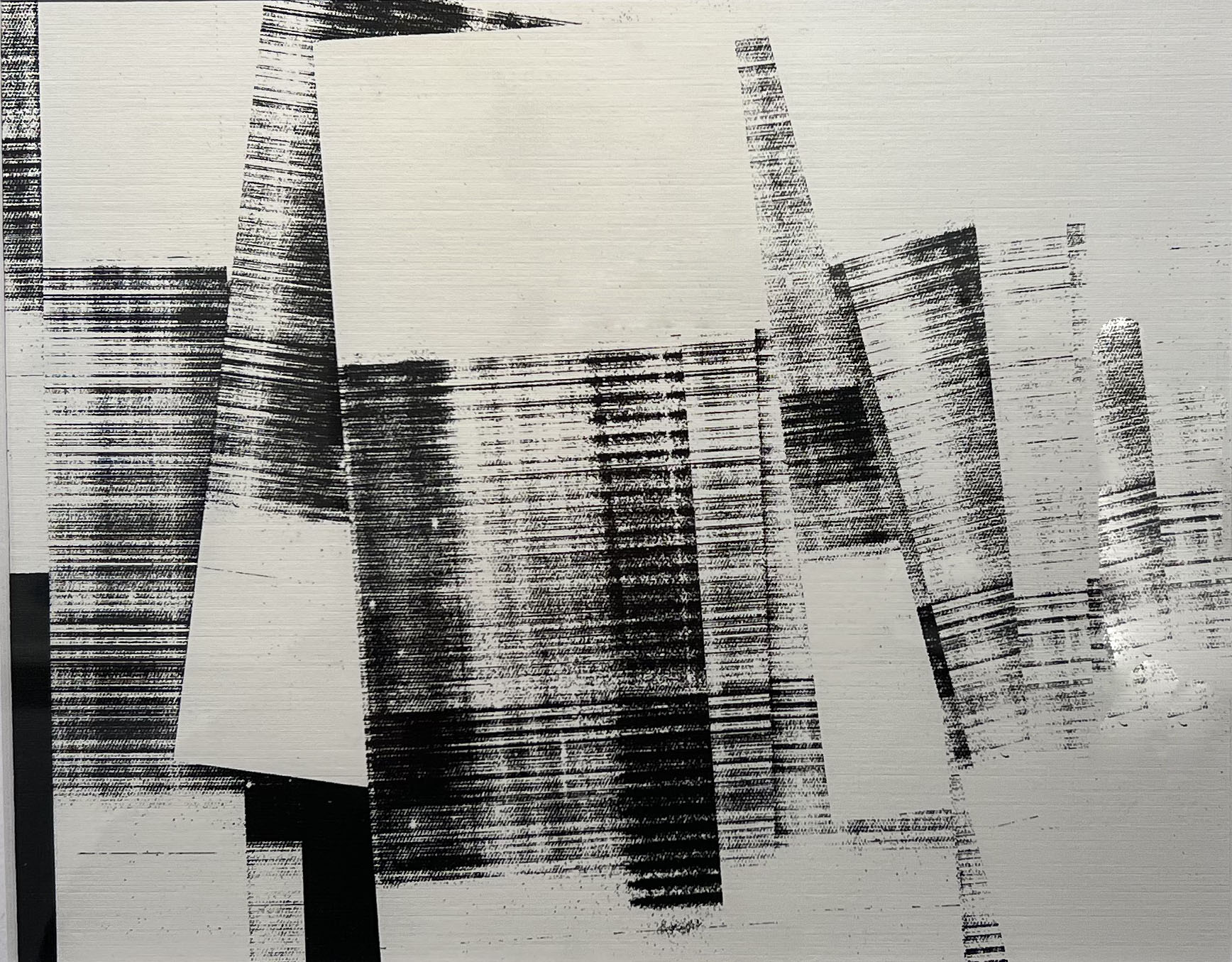

Maria Balogna, Darkness to Light III, Ink on Paper

“The Cost. The Wounds. The Enormity. Symbolic themes run throughout this collection of small drawings that outwardly express the salvific work of The Suffering Servant [ reference: Isaiah 53 ].” The abstract drawings of Maria Balogna contain undertones of Christianity without the weight of literary imagery.

The exhibitions will run through April 20, 2023.

The BBAC is open to the public. Masks are strongly recommended.

EXHIBITION GALLERY HOURS: Monday-Thursday 9 am-5 pm, Friday & Saturday, 9am-4 pm